Today there is an article in the Washington Post that describes a genetic site that may be the source of schizophrenia.

The researchers, chiefly from the Broad Institute, Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, found that a person’s risk of schizophrenia is dramatically increased if they inherit variants of a gene important to “synaptic pruning” — the healthy reduction during adolescence of brain cell connections that are no longer needed.

In patients with schizophrenia, a variation in a single position in the DNA sequence marks too many synapses for removal and that pruning goes out of control. The result is an abnormal loss of gray matter.

For years that has been a search for the reason why this mental illness appears in adolescence in people who seemed normal until that stage of development. It is known that adolescence is the time for”pruning” of excessive neuron synapses. Now, it seems that this may be the target f the genetic defect.

The fact that the answer might come from genetics has been known for a while.

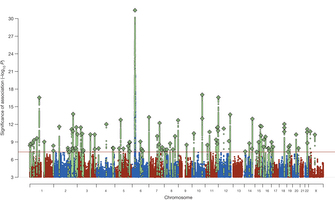

To date, around 30 schizophrenia-associated loci10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 have been identified through GWAS. Postulating that sample size is one of the most important limiting factors in applying GWAS to schizophrenia, we created the Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC). Our primary aim was to combine all available schizophrenia samples with published or unpublished GWAS genotypes into a single, systematic analysis24. Here we report the results of that analysis, including at least 108 independent genomic loci that exceed genome-wide significance. Some of the findings support leading pathophysiological hypotheses of schizophrenia or targets of therapeutic relevance, but most of the findings provide new insights.

The new paper, just out yesterday in epub, has narrowed the search to the C4 gene on chromosome 6.

After conducting studies in both humans and mice, the researchers said this new schizophrenia risk gene, called C4, appears to be involved in eliminating the connections between neurons — a process called “synaptic pruning,” which, in humans, happens naturally in the teen years.

It’s possible that excessive or inappropriate “pruning” of neural connections could lead to the development of schizophrenia, the researchers speculated. This would explain why schizophrenia symptoms often first appear during the teen years, the researchers said.

This is huge news. I have a chapter on my own experiences in treating schizophrenic men in the early 1960s in my book, War Stories: 50 years in medicine.

My teacher, George Harrington, told me he thought schizophrenia had to be organic in origin and he speculated that it could be deficiency of an unknown vitamin. Genetics were very primitive in those days. The discovery of the number of human chromosomes had only recently been announced when I began medical school. The number was only discovered in 1956, six years before I began medical school.

Using postmortem human brain samples, the researchers found that variations in the number of copies of the C4 gene that people had, and the length of their gene, could predict how active the gene was in the brain.

The researchers then turned to a genome database, and pulled information about the C4 gene in 28,800 people with schizophrenia, and 36,000 people without the disease, from 22 countries. From the genome data, they estimated people’s C4 gene activity.

They found that the higher the levels of C4 activity were, the greater a person’s risk of developing schizophrenia was.

The researchers also did experiments in mice, and found that the more C4 activity there was, the more synapses were pruned during brain development.

This is not therapy by any means but it is a huge step toward something that may prevent the disease is susceptibles.