Today is the second Monday in October and, since 1934, it has been celebrated as “Columbus Day.” The original celebration was political, to honor Italian immigrants who had come during the previous 40 years. However, Columbus was from Genoa, which was an independent republic until Italy was unified in the 19th century. He sailed for Spain after having been turned down by the Portuguese royal family, which was content with its African routes to India.

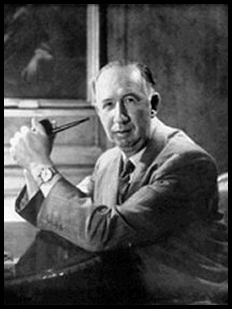

The best history of Columbus was written by Samuel Elliot Morrison, Harvard historian and sailor who would write the history of the

the US Navy in World War II.

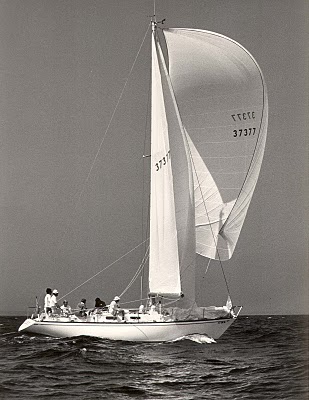

His Columbus history is a great work and involved a number of voyages by Morrison and colleagues who repeated Columbus voyages relying on original documents to duplicate his routes as best they could.

To research a biography of Christopher Columbus, Morison spent five months aboard a three-masted sailing ship, retracing the explorer’s routes 10,000 miles across the Atlantic and around the Caribbean. The resulting book, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus (1942), made Morison’s name as a scholar who was not content to dwell in the archives. It also gave him entree. “That Columbus book…brought me a welcome from sailors everywhere,” he once said. “It did me more good than the [naval] commission. Columbus was my passport.”

It helps to be a sailor to understand what Morrison was doing with Columbus. He was already a sailor and knew enough about the sea to recognize how Columbus would go about his task.

In 1940, Morison published Portuguese Voyages to America in the Fifteenth Century, a book that presaged his succeeding publications on the explorer, Christopher Columbus. In 1941, Morison was named Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History at Harvard. For Admiral of the Ocean Sea (1942), Morison combined his personal interest in sailing with his scholarship by actually sailing to the various places that Christopher Columbus explored. The Harvard Columbus Expedition, led by Morison and including his wife and Captain John W. McElroy, Herbert F. Hossmer, Jr., Richard S. Colley, Dr. Clifton W. Anderson, Kenneth R. Spear and Richard Spear, left on 28 August 1939 aboard the 147 foot ketch Capitana for the Azores and Lisbon, Portugal from which they sailed on the 45 foot ketch Mary Otis to retrace Columbus’ route using manuscripts and records of his voyages reaching Trinidad by way of Cadiz, Madeira, and the Canary Islands.[8] After following the coast of South and Central America the expedition returned to Trinidad on 15 December 1939.[8] The expedition returned to New York on 2 February 1940 aboard the United Fruit liner Veragua.[8] The book was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1943.

He drew the outline of islands as they approached them and compared his drawings to those of Columbus that could still be found. The same technique in recognition is still used in cruising publications for amateur sailors.

GPS has replaced a lot of the navigational methods used by tradition but the US Navy has returned to training deck officers in celestial navigation.

But now the US navy is reinstating classes on celestial navigation for all new recruits, teaching the use of sextants – instruments made of mirrors used to calculate angles and plot directions – because of rising concerns that computers used to chart courses could be hacked or malfunction.

“We went away from celestial navigation because computers are great,” said Lt. Cmdr. Ryan Rogers, the deputy chairman of the naval academy’s Department of Seamanship and Navigation. He told Maryland newspaper The Capital Gazette: “The problem is there’s no backup.”

Most of Columbus’ navigation was “Dead Reckoning” as celestial navigation was primitive at the time he sailed. Latitude sailing was the most reliable method before longitude could be determined. The navigator would sail, often by coastal methods, until reaching the latitude of the destination, then sail east or west along that latitude until the destination was reached. Columbus used this method although his latitude measurements were greatly in error.

Middle-latitude sailing combines plane sailing and parallel sailing. Plane sailing is used to find difference of latitude and departure when course and distance are known, or vice versa. Parallel sailing is used to interconvert departure and difference of longitude. The mean latitude (Lm) is normally used for want of a practical means of determining the middle latitude, or the latitude at which the arc length of the parallel separating the meridians passing through two specific points is exactly equal to the departure in proceeding from one point to the other. The formulas for these transformations are:

DLo = p sec Lm and p = DLo cos Lm.

The mean latitude (Lm) is half the arithmetic sum of the latitudes of two places on the same side of the equator. It is labeled N or S to indicate its position north or south of the equator. If a course line crosses the equator, solve each course line segment separately.

This is more complicated as it assumes two latitudes, origin and destination. Columbus knew that the Canary Islands were on the same latitude as China, where he planned to end his voyage. His estimate of longitude was far off, by about 30 degrees. He did not know of the existence of America but began, by his fourth voyage, to realize that he had discovered a New World.

His navigational skills were incredible, given the time. He was able to return to Spain, although his first landfall was Portugal as he encountered heavy weather on the return. He made a total of four voyages and returns. He was less successful as a colonial administrator than navigator but his accomplishments as sailor and navigator are enormous.