This will be the final installment of the history. It is in parts because WordPress starts to drop text if the pst gets too long.

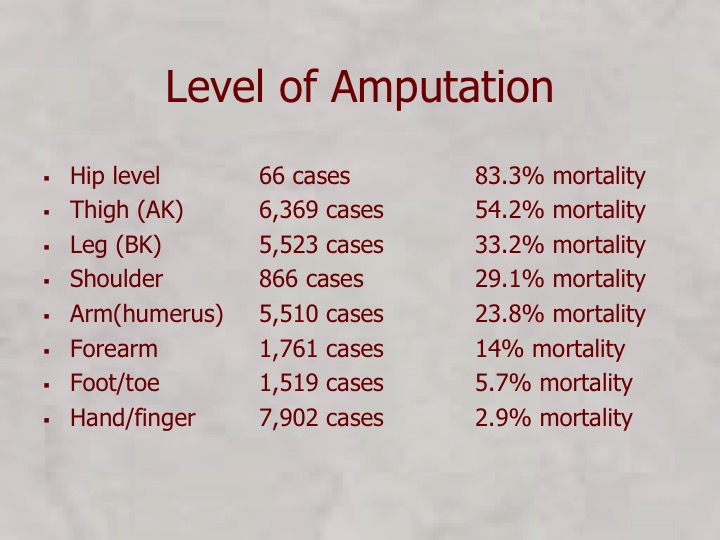

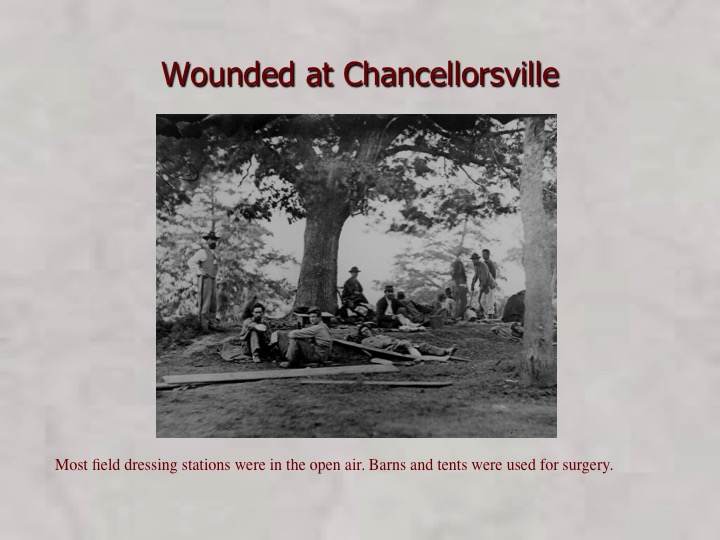

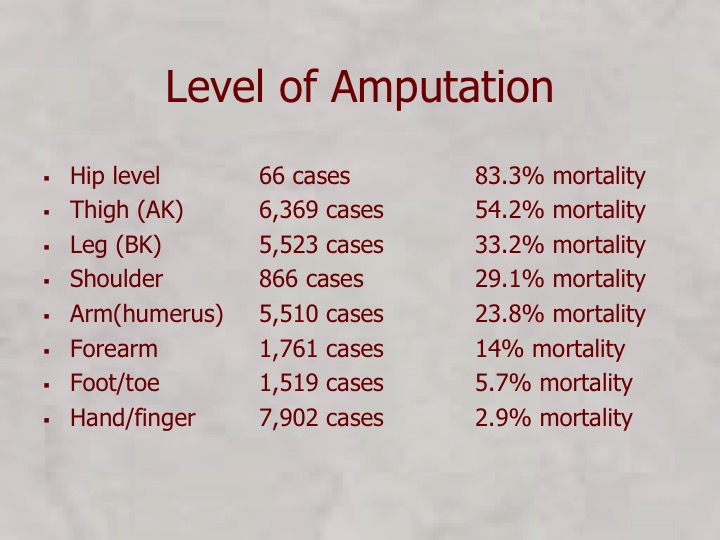

Amputations were the most common procedures for war wounds. Below knee amputations had about a 33% mortality. Most deaths were from infection and wound shock, which was a mystery until World War I.

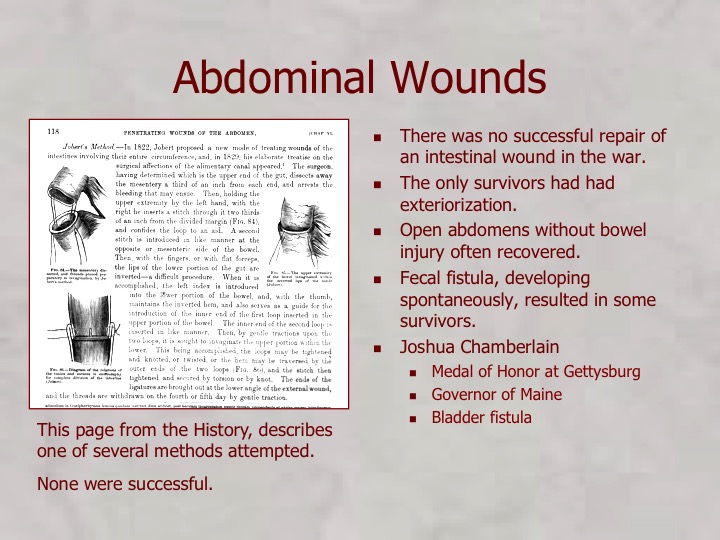

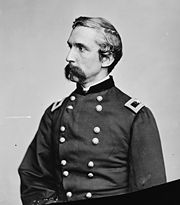

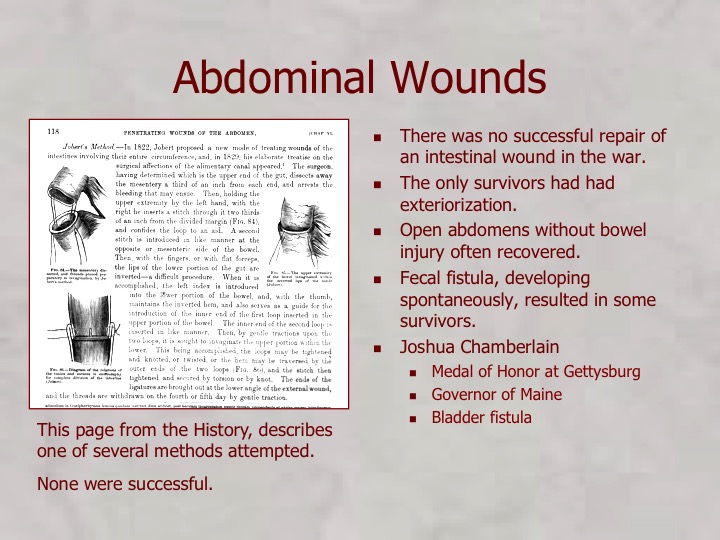

Abdominal wounds were mostly fatal although there were survivors. One of the survivors was Joshua Chamberlain, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for conspicuous bravery at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Chamberlain was a survivor of an abdominal wound and, like many, was left with life-long disability. He had a bladder fistula that continuously drained urine the rest of his life.

Chamberlain offered his services to the governor of Maine who appointed him Lieutenant Colonel of the newly raised 20th Maine regiment. The scholar-turned-soldier would take advantage of his position as second-in-command and studied “every military work I can find” under the close tutelage of his commander, West Point graduate Col. Adelbert Ames.

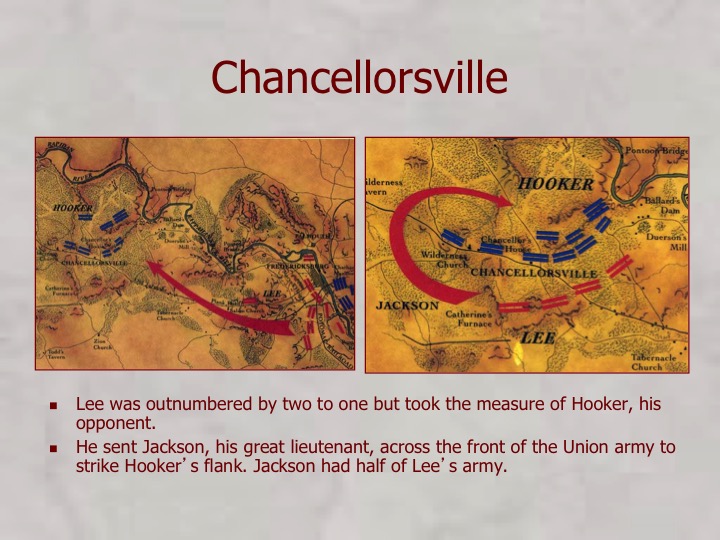

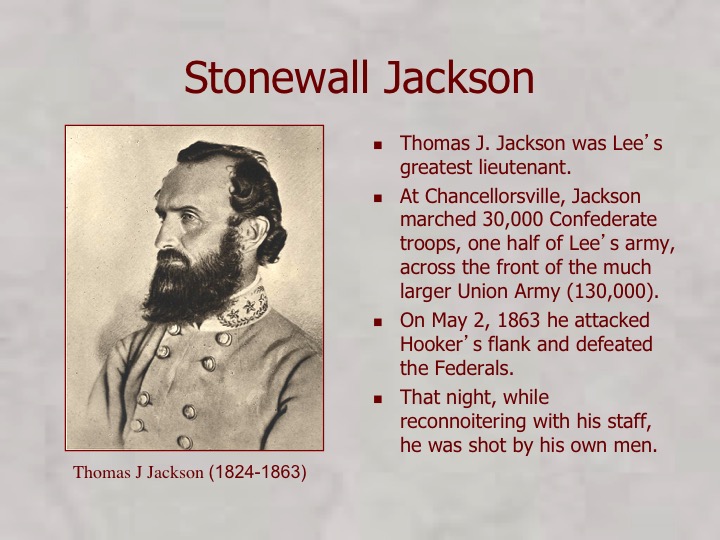

Though present at Antietam, Chamberlain and his regiment saw their first trial by fire in one of the doomed assaults on Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg but missed a chance to be involved at the Battle of Chancellorsville due to an outbreak of smallpox. Losses at Chancellorsville elevated Col. Ames to brigade command, leaving Chamberlain to command the regiment in the next major engagement of the war, the Battle of Gettysburg.

On July 2, 1863, Chamberlain was posted on the extreme left of the Federal line at Little Round Top—just in time to face Confederate General John B. Hood’s attack on the Union flank. Exhausted after repulsing repeated assaults, the 20th Maine, out of ammunition, executed a bayonet charge, dislodging their attackers and securing General Meade’s embattled left. Though the exact origin of the charge is still the subject of debate, Congress awarded Chamberlain the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry.”

He received a bullet wound in the battle of Petersberg that left him with a permanent disability. Even so, he had a successful career. He was wounded six times in all.

After the war, Chamberlain returned to Maine, where he served four terms as the state’s Governor. He later served as president of Bowdoin College alongside former general and Bowdoin alum, Oliver Otis Howard. Prolific and prosaic throughout his life, Chamberlain spent his twilight years writing and speaking about the war. His memoir of the Appomattox Campaign, The Passing of the Armies was published after his death in 1914.

His wound was ultimately fatal.

His old wound became infected in 1914, and on Feb. 24, at age 85, Joshua Chamberlain, the very model of a citizen soldier, died. He was the last Civil War veteran to die of wounds sustained in battle.

He wrote that Army Manual of Leadership, FM -6-22 which is still in use.

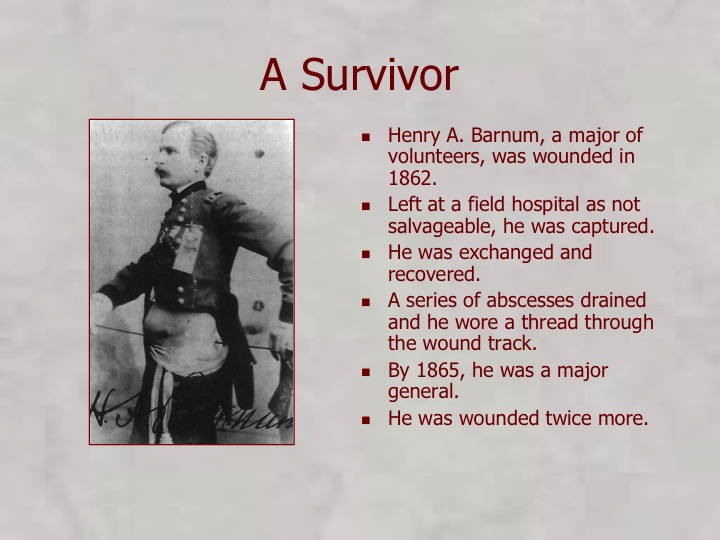

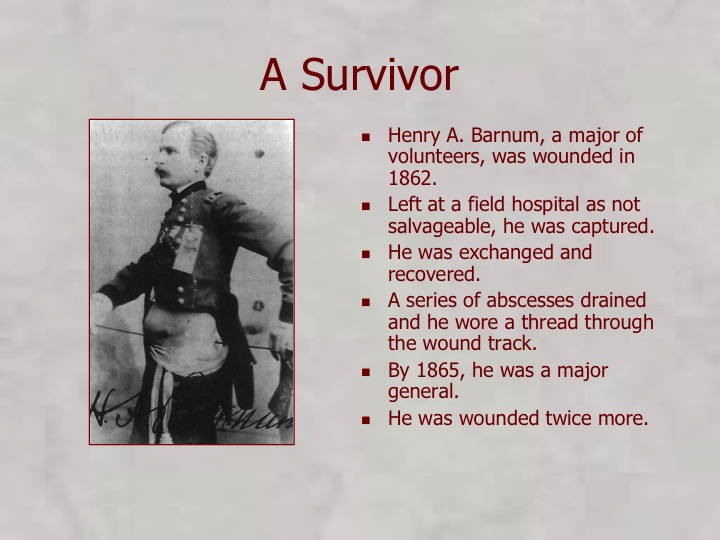

Another example of a survivor is Major Henry A. Barnum, a Major of Volunteers who ended the war as a Major General.

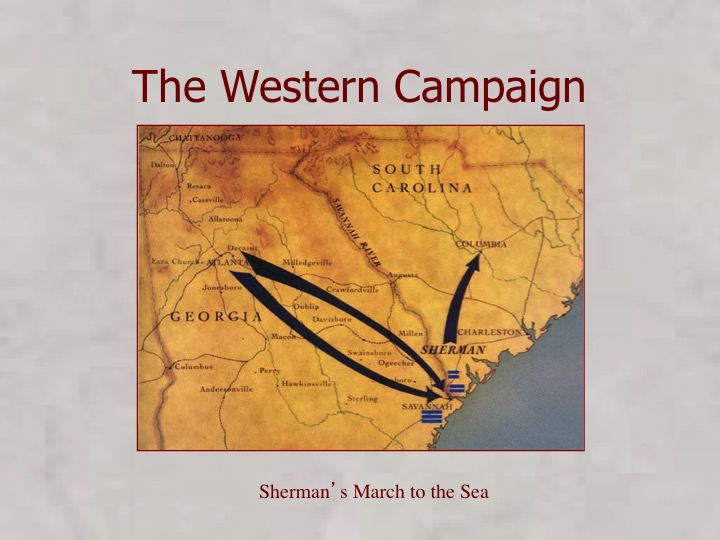

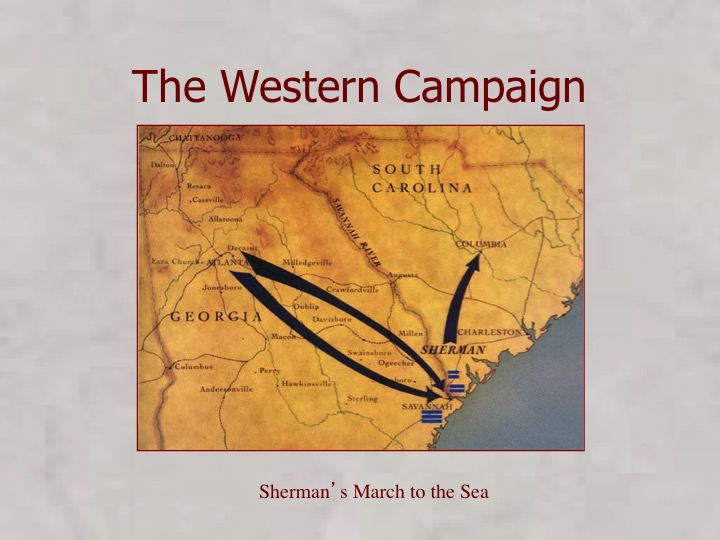

The Western Campaign brought forth General William T Sherman, who is in my opinion the greatest American general since Washington, who was really more of a political leader.

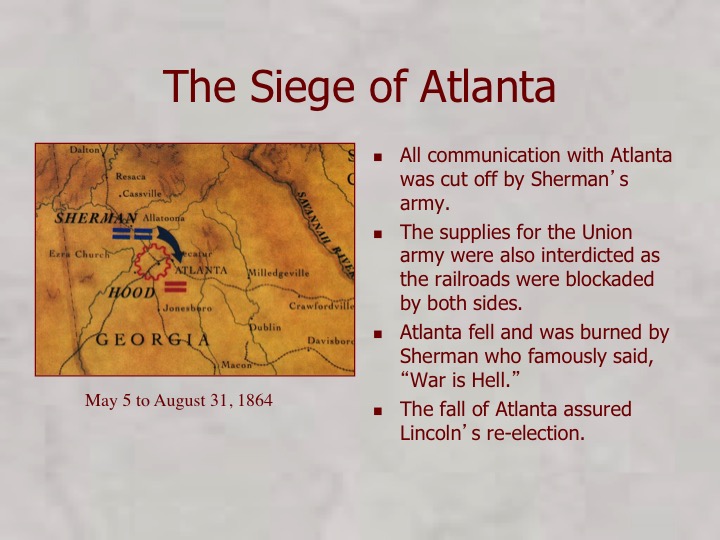

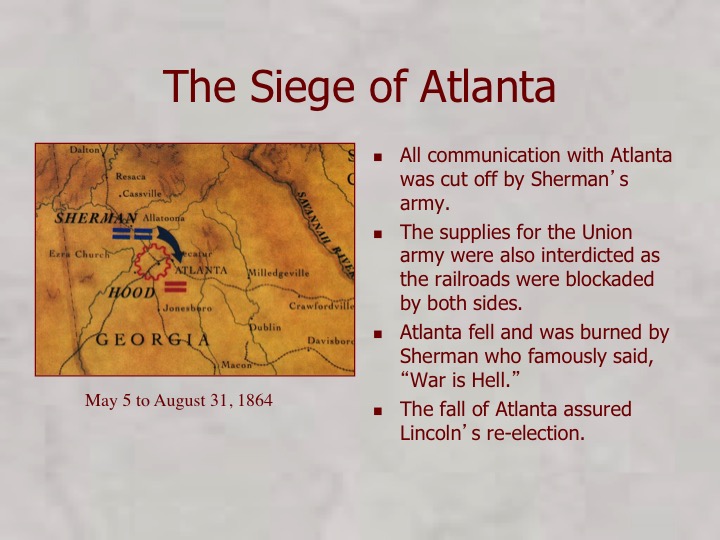

Sherman led his army across Georgia after the successful siege of Atlanta which assured Lincoln’s re-election in 1864.

The Siege of Atlanta, which was followed by the burning as depicted in “Gone With The Wind.”

During the siege, instances of Scurvy rose among Sherman’s soldiers and in the residents under siege, Once the siege ended and trains resumed bringing fresh fruit and vegetables, the scurvy declined.

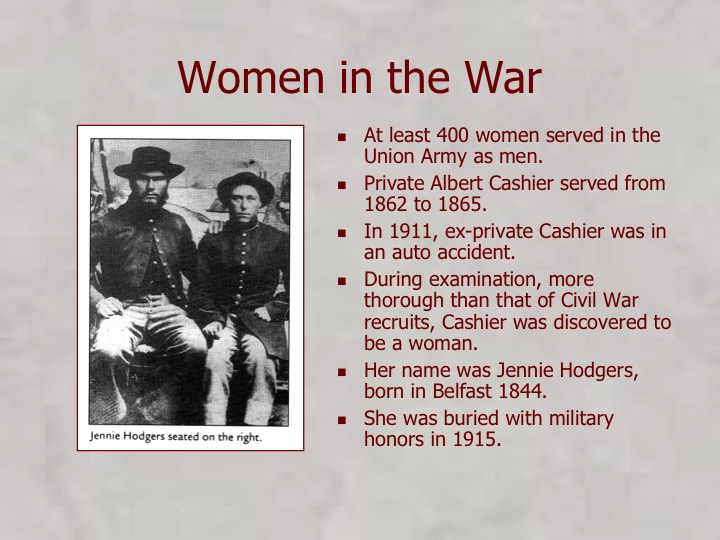

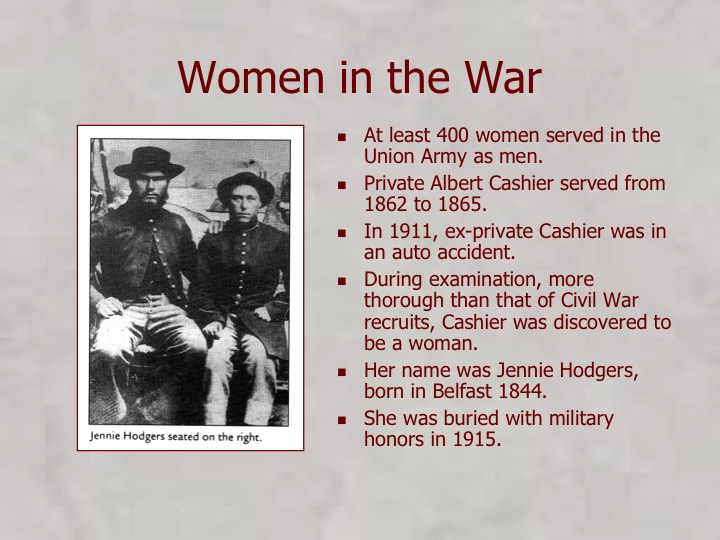

Women played various roles in the war. One captured Confederate officer, while in a prisoner of war camp in Ohio, delivered a child in spite of the fact that she had campaigned and been captured as a male officer. Her husband was also a Confederate officer.

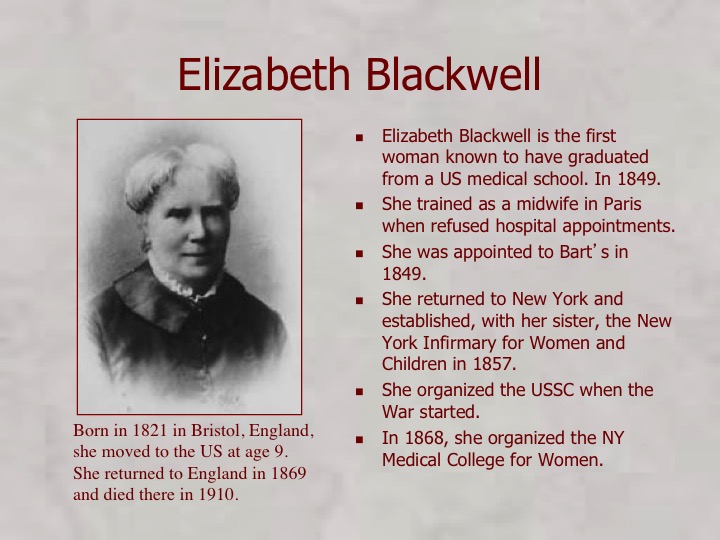

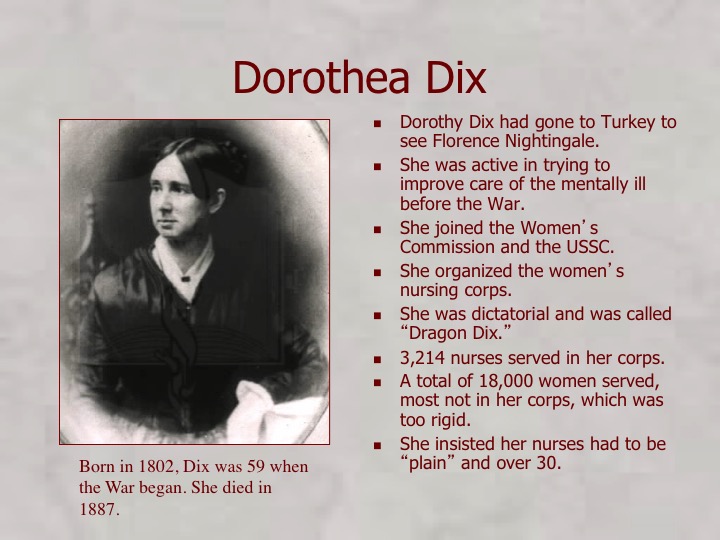

Elizabeth Blackwell was the first American female medical school graduate. She was instrumental in the founding of the US Sanitary Commission, which was modeled on a similar British Commission during the Crimean War. Her organization was called, “the Women’s Central Relief Association of New York,” and had Dorothea Dix as its head.

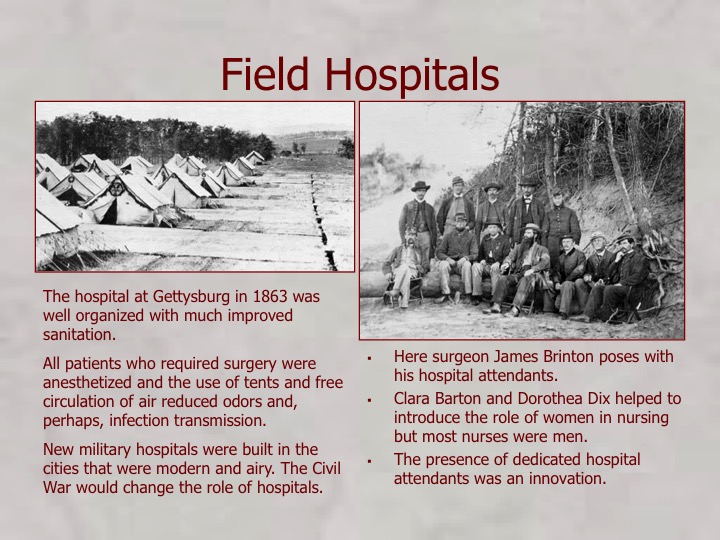

Dix was a well known health reformer who had previously worked on the treatment of mental illness. She began to recruit female nurses although most nurses during the war were male.

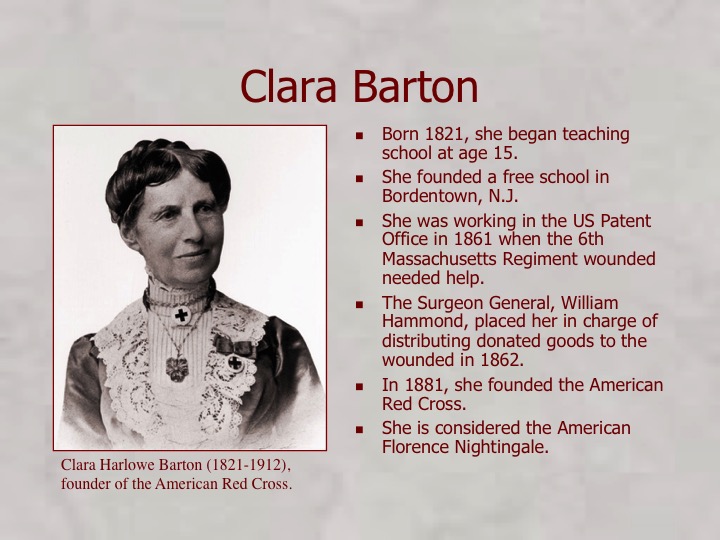

Clara Barton was working in DC when she saw wounded men making their own way into the city after the battle of Bull Run. She organized relief supplies. The Surgeon General, William Hammond, placed her in charge of distributing donated goods to the wounded in 1862.

In 1881, she organized the American Red Cross.

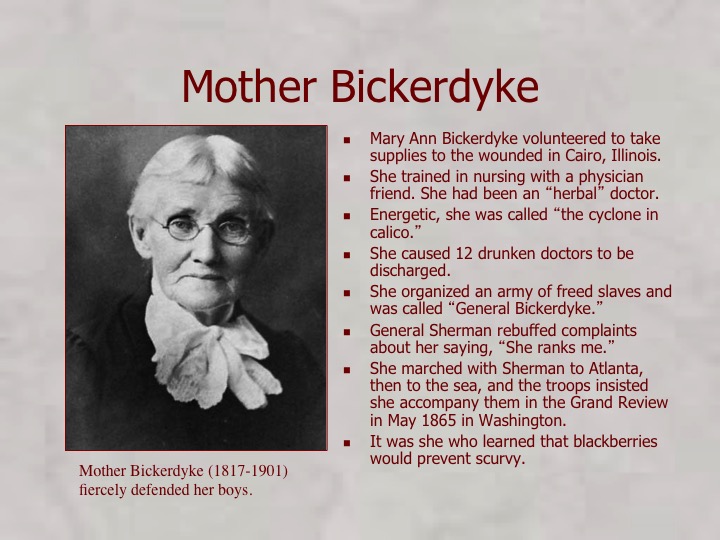

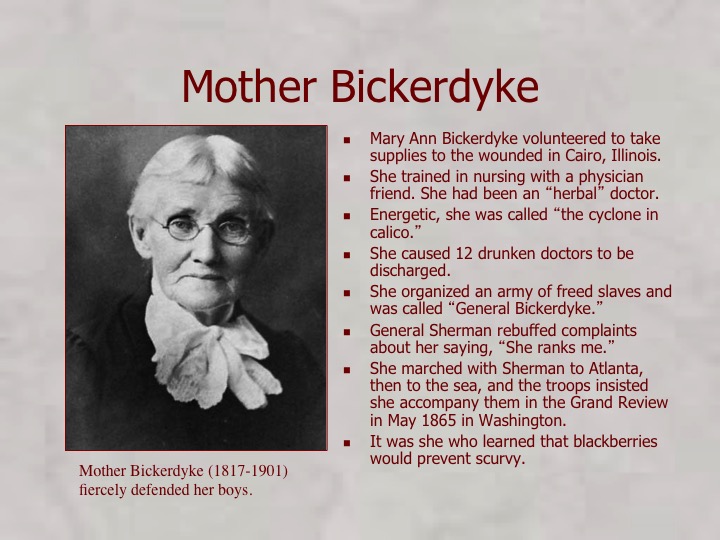

Mother Bickerdyke is a little known but hugely important member of Sherman’s army. She began as a volunteer in Illinois, joined his army and marched all the way to Savannah with the army. They insisted she accompany them in the Grand March in Washington City after the war. She organized field kitchens and bakeries to feed the troops. She organized freed slaves to build her kitchens and field hospitals. It was she who discovered that black berries, growing wild in the South, would prevent scurvy.

After the war ended, Bickerdyke was employed in several domains. She worked at the Home for the Friendless in Chicago, Illinois in 1866. With the aid of Colonel Charles Hammond who was president of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad, she helped fifty veterans’ families move to Salina, Kansas as homesteaders. She ran a hotel there with the aid of General Sherman. Originally known as the Salina Dining Hall, it came to be called the Bickerdyke House. Later, she became an attorney, helping Union veterans with legal issues including obtaining pensions.

Congress had made no provision for pensions or the care of wounded veterans. Mary Ann Bickerdyke worked with Sherman to employ veterans on the railroad that was crossing the plains and to provide care of those wounded and the families of the dead. She and Sherman establish what would eventually became the Veterans Administration. Sherman’s friend and associate General Grenville Dodge was the Chief Engineer for the Union Pacific Railroad.

In May 1866, he resigned from the military and, with the endorsement of Generals Grant and Sherman, became the Union Pacific’s chief engineer and thus a leading figure in the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad.[3]

Dodge’s job was to plan the route and devise solutions to any obstacles encountered. Dodge had been hired by Herbert M. “Hub” Hoxie, a former Lincoln appointee and winner of the contract to build the first 250 miles of the Union Pacific Railroad. Hoxie assigned the contract to investor Thomas C. Durant who was later prosecuted for attempts to manipulate the route to suit his land-holdings.[3] This brought him into vicious conflict with Dodge and Hoxie. Eventually Durant imposed a consulting engineer named Silas Seymour to spy and interfere with Dodge’s decisions.

Seeing that Durant was making a fortune, Dodge bought shares in Durant’s company, Crédit Mobilier, which was the main contractor on the project. He made a substantial profit, but when the scandal of Durant’s dealings emerged, Dodge removed himself to Texas to avoid testifying in the inquiry.