Genetic engineering may have explained the mortality of the 1918 flu. Apparently, three genes are responsible for the viruses ability to infection lung and not just bronchus.

“We wanted to know why the 1918 flu caused severe pneumonia,” Kawaoka said in a statement.

They painstakingly substituted single genes from the 1918 virus into modern flu viruses and, one after another, they acted like garden-variety flu, infecting only the upper respiratory tract.

But a complex of three genes helped to make the virus live and reproduce deep in the lungs.

The three genes — called PA, PB1, and PB2 — along with a 1918 version of the nucleoprotein or NP gene, made modern seasonal flu kill ferrets in much the same way as the original 1918 flu, Kawaoka’s team found.

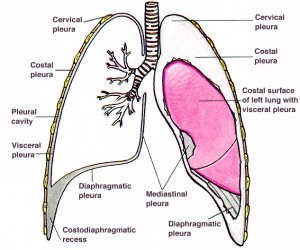

There was a second reason for the high mortality in 1918-1920. The principles of thoracic surgery, including the physiology of respiration were not understood at the time. Thousands of flu cases, those with pneumonia, developed a secondary bacterial pneumonia and then developed empyema. Empyema is a collection of infected fluid in the space between the lung and the chest wall. We now know how to treat this condition. The principles of treatment are here. Note the observation that Hippocrates understood the principle of empyema; namely that thin fluid in the collection could be drained by an opening in the chest wall but the patient would die. Hippocrates didn’t understand why. The knowledge of lung physiology would not come until the 19th century. However, Hippocrates did observe that draining thick pus through an opening in the chest did not result in the death of the patient in all cases, as it did in those where the fluid was thin and watery. What was the reason ?

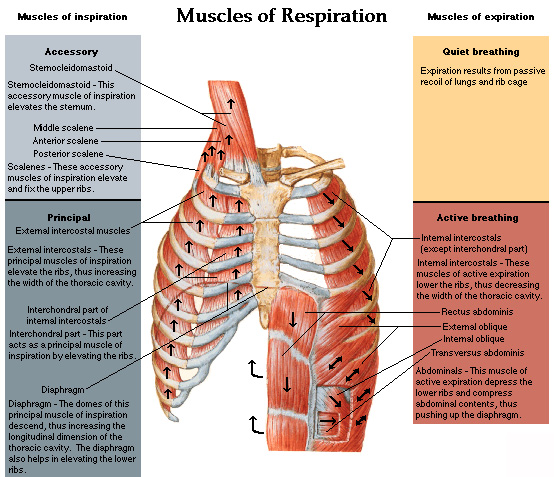

We now know that a relative vacuum exists between chest wall and lung. The chest wall is rigid and, during respiration, it changes its volume by using the “bucket handle effect” of the ribs.

The space between lungs and chest wall is shown along with the general anatomy. That space is what fills with fluid in cases of pneumonia that develop empyema.

The ribs are curved and, when the muscles of the chest wall pull up on them, as shown by the arrows, the cross section of the chest cavity increases because of the “bucket handle” effect. With expiration, the ribs move back down and the volume of the chest cavity decreases. This volume shift, aided by the piston effect of the diaphragm, moves air in and out of the chest. The lungs are not attached to the chest wall, allowing them to slide up and down and accommodate their shape to the shape of the chest wall. If there is a hole in the chest wall, the air can move into the space between the lung and chest wall, collapsing the lung. This is called a “sucking chest wound” in trauma care. If the hole in the chest wall is larger than the trachea, air will move more easily in and out of the chest and respiration through the trachea will stop. This was the great barrier to chest surgery that was not overcome until the 1920s. The flu epidemic, and the research into the cause of death in so many cases, led to the understanding of how the chest works.

I recently reviewed a book about the history of the 1918 flu epidemic and, because it ignored the issue of empyema, I could not finish it. They had only half the story. The story of empyema, and the cause and cure, resulted from work of the Empyema Commission, chaired by Evarts Graham, professor of surgery at Washington University of St Louis medical school. Here is one of many scholarly works describing his great accomplishment. Unfortunately, little of this has penetrated the general history of the epidemic in spite of 90 years. In a recent article about the military cases during the First World War, it states: During World War I, the overall empyema mortality rate among US military forces was 61%. The same, or greater, mortality was seen in the flu cases that occurred in the same period. Untreated empyema was virtually 100% fatal.

During World War I, empyema treated by thoracotomy was associated with a mortality of > 30%. This prompted the establishment of the Empyema Commission, which recommended chest tube drainage for treatment.

The surgeons who were treating the flu cases, just as those treating empyema due to war wounds, used the old Hippocratic treatment of draining the pus from the empyema. Note that in the war wound cases, 70% of these patients survived. The flu cases were different and almost all died in a few hours after the fluid was drained. The difference was that the empyema in flu cases was due to streptococcus infection, which produces a thin fluid and does not cause the lung to stick to the chest wall. When the chest was opened, the lung collapsed and these already sick patients succumbed. Hippocrates had predicted this. The war wound cases did better because the staph infections of the pre-antibiotic days (“Laudable pus”) caused the lung to stick to the chest wall and it would not collapse.

Eventually, Graham learned that using a tube instead of an open hole to drain the pus, and placing the chest tube under water at its lower end, would seal the air leak but allow drainage of the pus. His work opened the door to thoracic surgery and, today, would save most of the cases in a new flu epidemic. Graham was also the first to warn of the association between smoking and lung cancer, a disease he was to die of 1957. He performed the first successful removal of a lung for cancer and his patient attended his funeral 24 years later.

Genetics is a powerful tool in the treatment of disease but physiology is still as important. Scientists understand the first but may not be aware of the other factors. There is no substitute for the experience of treating patients.