The Republican convention of 1920 knew that the party was heavily favored to win the fall election. Wilson was forlornly hoping for third term nomination in spite of his crippled state as a result of the stroke. Teddy Roosevelt had died in 1919 at the age of 60. The contenders on the Republican side included Illinois Governor Frank Lowden whose only major handicap with the voters was the fact the he had married the daughter of George Pullman, the railroad tycoon, and was rather ostentatious in displaying his wealth. He had, however, been a reform governor of Illinois. General Leonard Wood, who had been a medical officer commissioned into the regular army in 1886 as a line officer, was another. He had been the senior officer of the US Army in 1917, yet President Wilson had appointed John J. Pershing, junior to Wood, to the European command. Wilson considered Wood a potential political rival, somewhat like Harry Truman and Franklin Roosevelt considered General MacArthur.

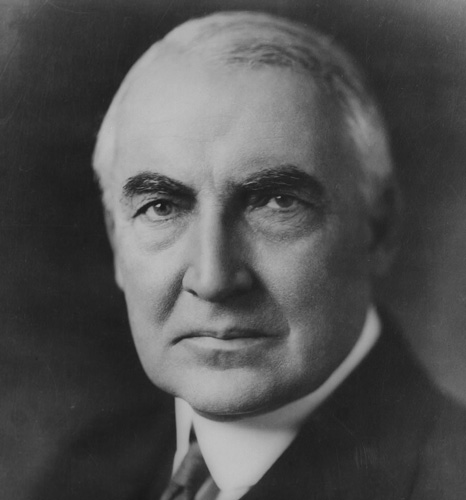

The third contender was Hiram Johnson, who had run as Teddy Roosevelt’s VP candidate on the Progressive ticket in 1912. There was little enthusiasm for him except among former Progressives who had returned to the party for 1920. Warren Harding is often described as a dark horse who was selected by party bosses after the leaders had exhausted each other. In fact, he was always in the top four and his selection was not a surprise to the convention.

The huge surprise was the nomination of Coolidge for Vice-President. He did not seek the nomination and was not interested after his experience as lieutenant governor of Massachusetts. After the Boston Police Strike, his name was familiar to the nation and in a favorable way. A big issue was the League of Nations and Coolidge favored membership, although with the Lodge reservations. Senator Lodge, no ally of Coolidge, exchanged letters with him on the League and agreed to disagree. Nevertheless, Lodge offered to place Coolidge’s name in nomination for President. Why he made the offer is not know. After several very favorable newspaper profiles appeared in early 1920, Coolidge made another statement that he was not a candidate for President. Frank Stearns and Lodge tried to bring a Coolidge delegation to the convention but Wood lived in Massachusetts and the delegation split. His interest in the nomination was further diminished by the death of his beloved step-mother, Carrie in May 1920.

Lowden’s handlers favored Coolidge as a VP candidate as he and the governor were from different parts of the country. Lowden’s biggest problem with the bosses was his reputation as incorruptible. The Illinois party bosses distrusted him. They feared he couldn’t be bought, or if so, wouldn’t stay bought. Robert Sobel, in his biography of Coolidge, says that Lowden was probably the best qualified Republican of the 1920s. One of the party bosses, Boies Penrose, asked Harding if he wanted to be president. Harding liked being a Senator and declined, leading Penrose to look elsewhere. By the time of the convention, Penrose was fatally ill, although his reputation was still powerful. He awakened from a coma during the convention, asked about the voting and suggested they choose Harding. Then, he lapsed into the coma again.

There were 16 primaries in 1920 but they held little power in the nomination. General Wood won the New Hampshire contest and Hiram Johnson won North Dakota. In the end, the primaries were indeterminate and Wood alienated some potential supporters by entering primaries where a favorite son preferred to keep the delegation united. Harding won as a favorite son in Ohio but Wood also took some delegates and Harding was not optimistic about his chances. Harry Daugherty, his manager, pressed him to keep his options open. Two considerations remained. Ex-soldiers were becoming disillusioned by the results of the war and women would vote for the first time in a national election. A soldier and a rich man might have trouble with those groups. Hiram Johnson was a progressive and anathema to the bosses, plus he did not have Roosevelt’s personality and charisma.

It was not just pique that caused the party bosses to hate Johnson. In 1916, he refused to support Charles Evans Hughes, the GOP candidate, and Hughes lost California, re-electing Wilson. Much history turned on that decision by Johnson as the US entered the war the next year.

[ I will insert a medical note here. Hughes’ daughter, Elizabeth, developed diabetes before the discovery of insulin. She was first treated by a Doctor Frederick Allen who had developed a theory that diabetics could be treated by competely eliminating glucose and sucrose from their diet. This was based on observations during the First World War where diabetics tolerated starvation better then the non-diabetics. The problem was that the children lost weight, craved sugar and were starving although they did not go into diabetic coma. Fortunately, Banting discovered insulin in 1921 and Elizabeth was one of his first patients (after Leonard Thompson, his first). When she began insulin, she was 14 years old and weighed 54 pounds. She lived to the age of 74 and many of her family were unaware of her diabetes as she injected herself each day.]

There is a famous story that reporters came to Hughes’ house on election night to interview him. The Hughes people were so certain he had been elected that they told the reporters that “the President is asleep.” The riposte was “When he wakes up, tell him he isn’t President.” None would forget Johnson’s role in that fiasco.

The campaign was so acrimonious that it was unlikely that any of the front runners could combine forces. Harding had not challenged favorite sons in primaries. Daugherty actually predicted the convention result to reporters, saying that at “eleven minutes after two, Friday morning of the convention, when ten or twenty weary men are sitting around a table, someone will say, “Who will be nominated ?”

Harry Daugherty and Harding.

There were huge problems for the country, of which the League of Nations was a minor one. The end of the war had brought a severe recession/ depression with 25% unemployment and a shrinking GDP. Inflation had outpaced wages but wage increases were out of the question with 25% unemployment. The remaining Progressive agenda, including Prohibition, which most Republicans opposed, was another issue. Johnson was an ardent isolationist; Wood was more internationalist, and Lowden was more concerned with the economy. This mattered less for the nomination as the decision would be made on political issues. Coolidge was a long, long shot as a favorite son presidential candidate and his organization at the convention was rudimentary. Stearns was a novice in national politics and Coolidge’s other supporters, including Dwight Morrow, had little influence. Crane had been very ill and would play no more role in Coolidge’s career.

The leading candidates canceled each other out and there was a mini-scandal about campaign funds which harmed both but did not help Johnson. The Literary Digest polled its readers, the precursor of modern polls, and found that Wood led Johnson with 277,486 vs 266,087. Coolidge received 33,621 votes and Harding little more. At 11 pm Thursday, the bosses sent for Harding. He was asked if there was anything in his past that would be a problem. His mistress and mother of his illegitimate child was in Chicago with him but he assured them that he was clean. Messages were sent to the other candidates’ headquarters telling them that Harding was to be the nominee but they did not surrender meekly. Wood and Lowden attempted to broker a deal but the campaign had been so bitter that neither could deliver delegates to the other.

The convention reconvened at 10 am. Voting recommenced and the trend was now toward Harding. On the tenth ballot, he was elected with 692 1/2 voted to Wood’s 156 and Johnson’s 80 1/2. Coolidge still received five votes on the final ballot. Now, the convention was to turn to the vice-presidential nomination. Tradition had, and still has, the expectation that the presidential nominee will choose his vice-president. Harding’s choice was Senator Irvine Lenroot of Wisconsin. Irving Lenroot had been a close confident of Robert LaFollette, his Wisconsin colleague. He flirted with the Progressives but broke with them over the war. His choice was not popular with conservatives because of his Progressive record and was equally unpopular with Progressives because he had broken with them. Furthermore, he didn’t want the nomination. Unsurprisingly, he preferred the Senate.

The convention delegates made this exercise in insider politics superfluous. They were hot and tired and wanted to get home. On the floor, Crane was trying to whip up interest in Coolidge as a VP candidate. Meanwhile, nomination and seconding speeches for Lenroot droned on. There was resistance to allowing the bosses to pick both nominees. Senator Lodge, tired and elderly, turned the gavel over to Ohio’s Frank Willis. An Oregon delegate asked for the floor. Assuming this would be another Lenroot seconding speech, Willis recognized him. Wallace MacCamant was something of a maverick and he was about to make history. He had read Coolidge’s speech “Have Faith in Massachusetts” which had been published in pamphlet form and widely circulated. The entire Oregon delegation were behind MacCamant as he made his fiery nomination speech for Coolidge. It energized the convention and was followed by a series of seconding speeches. One came from H.L. Remmel of Arkansas who had shortly before seconded Lenroot. It was, in part, a revolt against the bosses. Coolidge was seen as above the grubby business of politics with an absolutely clean record. Coolidge won on the first roll call. It was quickly made unanimous. Telegrams poured in including one from Wilson’s vice-president, Thomas Marshall.

The only real constituency that Coolidge had was the convention delegates who were about to disperse. Some speculated that, had he run a campaign at the convention, he might have been nominated for president. This was not Coolidge’s style. The party bosses were not supporters and he was not well known in the country. He had worked within the party machine in Massachusetts, always waiting his turn. Now he had been catapulted into the national scene but his solitary status would create many problems for him in the future.

Harding planned a “front porch campaign” similar to that conducted by his model, McKinley. In the meantime, the campaign began in a fashion that reminds some of Eisenhower in 1952. He was amiable, warm and decent but dull. The press reacted as they did to Eisenhower, considering him an amiable dunce. Harding, however, had been a well respected Senator and had been considered by Roosevelt as a possible VP nominee in discussions he had in 1919 before his death. It must also be added that Wilson was the ideal for intellectuals and progressives so that Harding would have no chance for a fair judgment. Arthur Schlessinger, in his history of the New Deal, slanders Harding as he did Coolidge with selective quotes and false statements. I will have more to say about that when I discuss Coolidge’s presidency. One example was a quote of Wilson’s Secretary of the Interior, Franklin Lane, who, writing in his death bed, mused about conditions in the country such as “the negroes being lynched, the miner’s civil war, labor’s holdups, employers’ ruthlessness, the subordination of humanity to industry..” The trouble was that Lane died in 1920 and Harding did not take office until 1921. Schlessinger omits this information. Lane was describing conditions under Wilson.

The entire period of the 1920s has been distorted and slandered by historians as they try to imply that it was a decade of excess under Republicans that led irreversibly to the Great Depression. All this was written later by historians, like Arthur Schlessinger, who adored FDR and condemned his predecessors for emphasis. In Nevins and Commager’s “A Pocket History of the United States,” the 1920s is described as “dull, bourgeois and ruthless.” “‘The business of America is business’,” said President Coolidge succinctly, and the observation was apt if not profound.” It was also an incomplete quote that distorted the meaning. They continue to describe the period so: “Never before, not even in the McKinley era, had American society been so materialistic, never before so completely dominated by the ideal of the marketplace or the techniques of the machinery.” Some of us might consider this a fair description of the Clinton era, as well, but, of course, the president’s party was not the same.

The Democrats chose James Cox of Ohio with a platform that, aside from endorsing the League of Nations, differed little from the Republican. For vice-president, they chose former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D Roosevelt. In 1920, few Americans were still enthusiastic about the war or the League of Nations. They had been hammered by wartime inflation and the economic collapse after. Wilson was still trying to maneuver for a nomination for a third time. Newspaper reporters were not very enthusiastic about Cox who was also a compromise candidate after 40 ballots. They called it “the kangaroo election” suggesting the hind legs were stronger than the front ones, a prescient description.

Coolidge traveled to Washington to meet with Harding; they knew each other slightly. He returned to Boston and, on “Notification Day,” July 27, he was officially informed of his nomination by a delegation from the convention. He gave a short speech of acceptance striking themes that were traditional for him. “The destiny, the greatness of America lies around the hearth stone. If thrift and industry are taught there, and the example of self-sacrifice oft appears, if honor abide there, and high ideals, if there the building of fortune be subordinate to the building of character, America will live in security, rejoicing in an abundant prosperity and good government at home, and in peace, respect and confidence abroad.” Crane, his mentor in Massachusetts politics, was in the audience but he died on October 2, not having the opportunity to see them win the election. Coolidge would miss his wisdom desperately in his presidency. Stearns was there but was not the adviser Crane would have been.

As the campaign began, Harding’s plan for a “front porch campaign” was shelved as Cox and Roosevelt began a very aggressive travel schedule. Originally, this was to be Coolidge’s role but he was not a very good speaker to crowds. During his presidency he would become the first president to use radio effectively but radio was still too primitive in 1920 and there was no such thing as a “broadcast.” Coolidge’s awkwardness as a speaker led the party to surround him with orators, including Lowden. A reporter asked Coolidge if he liked the campaign.”I don’t like it,” he replied. “I don’t like to speak. It’s all nonsense. I’d much better be at home doing my work (as governor).” He did go off message, telling voters that there was a better chance of America entering the League of Nations under a Republican administration than under the Democrats. What he meant by this was Wilson’s unwillingness to permit any (Lodge) exceptions in a bill to join the League. Wilson’s unwillingness to compromise is the real reason why the US never entered the League.

Harding and Coolidge received 16.1 million votes compared to 9.1 million for Cox and Roosevelt. Harding’s theme of “Return to Normalcy” was a popular one. Furthermore, he meant it. The Progressive agenda of Wilson was dead and its structures were quickly dismantled. Few women bothered to vote so the predictions based on their participation would have to wait for later elections. The Old South went solid Democratic, as usual, but Tennessee went Republican for the first time since 1868 and would not do so again until Eisenhower.

As the Coolidges prepared to move to Washington for the inauguration, they realized that housing would be a problem. There was no official residence for the vice-president. They could not afford the expensive city on the VP’s $12,000 salary and Coolidge refused an offer from Stearns to provide a leased home. They finally accepted an offer from outgoing Vice-President Marshall to turn over his two room apartment in the Willard hotel to them. It cost $8/ day and they accepted. They would remain there until he became president. In his acceptance speech in the Senate chambers, he praised the Senate and hoped to make friends but this was not to be. He had not been the Senate’s candidate and he was not the friendly, outgoing man his predecessor had been. Harding made good his promise to Coolidge that he would attend cabinet meetings and Coolidge learned a great deal during the next two years. His own presidency was to follow the Harding agenda right up to 1928.

Harding chose a strong cabinet, with two lethal exceptions. The party bosses who chose him wanted strong men around him as they perceived him to be weak. In fact, this went well with his own desires, not because he felt weak but because he wanted a strong cabinet. The Secretary of State was to be Charles Evans Hughes, presidential candidate of 1916 and a former Supreme Court justice. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon was a former banker and industrialist plus one of the world’s richest men. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover was a former successful businessman and a holdover from Wilson’s administration. He was world famous for his humanitarian work in Europe after the war.

Two of his cabinet members were disasters and may have caused his death. His campaign manager, Harry Daugherty, became Attorney General, not an unusual appointment but a disaster as it happened. Edwin Denby, Secretary of the Navy was not quite as bad but became enmeshed in scandal. Albert B Fall became Secretary of the Interior and the other disastrous nominee. At the time, there seem nothing wrong. Daugherty was hailed as a political genius for getting Harding elected. Denby had served in the Navy during the Spanish-American War, served in Congress on the House Naval Affairs Committee and enlisted in the Marine Corps as a private when the US entered World War I where he rose to major by the war end. His reputation is being rehabilitated recently.

Albert B Fall had served in the Spanish-American War and had been a Senator from New Mexico. He was considered an expert on Mexico, with which relations were terrible after Wilson’s interference and attacks on the Mexican government. Hughes had even suggested Fall for Secretary of State before the post was offered to him. It’s possible Fall might have stayed out of trouble as Secretary of State where opportunities for corruption were fewer.

Harding and Coolidge were opposites in personality, Harding being a joiner and made friends easily. He also had a string of extramarital affairs but they were discreet. His wife was older and ambitious but their marriage was cold. Their ideas on policy, however, were close and Coolidge continued Harding’s policies through his own presidency. Harding wished for compromise and hoped for consensus. He was not a leader and knew it. Coolidge had been a leader in Massachusetts but, curiously, was less so as president. Harding called a special session of Congress on April12, 1921, a month after the inauguration. He called for gradual liquidation of the war debt, slashing government spending and tax reduction from the high wartime rates. He advocated an increased tariff for manufacturing and agricultural products and asked Congress to set up a “national budget system,” a precursor of OMB and other economic policy agencies. He demanded lower railroad rates, a bete noir of farmers, and large scale highway construction, to be funded by the states.

Harding advocated a larger merchant marine and a larger Navy to protect the sea lanes. He supported the development of aviation and radio, both technological advances. He wanted increased restriction of immigration, an anti-lynching law, and a Department of Public Welfare. He ended his speech with an equivocal mention of the League of Nations which seemed to satisfy everyone, pro and con the League. Harding was a master of legislative relations. He held card parties, drank whiskey with Senators and socialized with possible opponents, which would be held against him later but which got his agenda enacted. When Coolidge succeeded Harding, he was fortunate that the agenda was in place and he did little to change Harding priorities. It was a highly successful program for the next decade.

Coolidge spent the next two years studying the federal government but had little otherwise to do. His chief contribution was representing the president at social functions. He wrote his father in 1921, shortly after the inauguration, that he and his wife were out to dinner three times a week. Grace Coolidge later said that her husband enjoyed the dinners at first but gradually wearied of them. They were the most senior guests so could leave early and were usually in bed by 10 o’clock. He gave speeches, most of which were bland, if not banal, but a few were interesting. In 1922 he gave a speech advocating employee stock ownership. “In the ideal industry, each individual would become an owner, an operator, and a manager, a master and a servant, a ruler and a subject.. This there would be established a system of true industrial democracy.”

Some of his speeches expressed his own philosophy. “people are not created for the benefit of industry, but industry is created for the benefit of the people.” These sentiments, of course, run counter to the false view promoted by hostile historians. Coolidge considered these two years as an education on government. He had been quite provincial but he met many people and traveled to many places as vice-president. He was not part of the inner circle in Washington, which might have been fortunate in retrospect. He wrote for magazines, an opportunity to develop his thoughts and acquire some additional income. Harding dropped the idea of using him as an assistant and confidant.

The administration did well in the early months. The Red Scare of Wilson’s Attorney General was ended. Treaties were negotiated. The Washington Naval Conference took place in November 1921. Disarmament was popular as the myth of war profiteers was given great credence in those days. Little Orphan Annie’s benefactor was Daddy Warbucks. Harding pardoned a number of people imprisoned during the war, including Socialist leader Eugene V Debs. He even invited Debs to the White House. His legislative agenda moved along. An immigration law was passed, which provided new restrictions. Charles G Dawes, a well know financial expert, was placed in charge of The Bureau of the Budget when enacted. A Veterans Bureau was established for war veterans. A proposed Veterans Bonus was vetoed, however. He supported Secretary Mellon’s proposal to cut tax rates but opposition was too strong. He reestablished relations with Columbia, healing the breach caused by the Panama Canal and the US interference in Columbia’s affairs.

Harding supported the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922. This was a protective tariff on agricultural imports. American farmers had seen agricultural prices rise as demand for agricultural products soared in the war and afterward until European agriculture could recover. Later, during Coolidge’s administration, this tariff would become counterproductive as Europe recovered but it was an article of faith with the Farm Bloc that formed in the 1920s. Harding pressed his friend, Elbert Gary, CEO of US Steel, to cut the 12 hour workday to 8 hours. The work week was sometimes 7 days a week and Harding pressed for this to be reduced, as well. Gary refused at first but eventually gave in by 1923.

In the early days of the Harding Administration, the country was in the grip of a severe recession that, had it lasted longer, would have earned the name Depression. In 1919-20 there were more than thirty thousand bankruptcies, half a million farm foreclosures and 5 million unemployed. On June 12, the day Harding and Coolidge were nominated, the Dow-Jones Industrial Average stood at 78.93. On Election Day, as business anticipated the new administration, it had risen to 85.23. In January 1921, before the new administration took charge, the unemployment rate was 20%. The GNP had dropped from $88.9 billion in 1920 to $74 billion in 1921, a decline of 1/6 in one year. There was little theoretical basis for measures to try to assist the recovery at the time but Harding asked Hoover to convene a conference on unemployment to consider what could be done for such a slump.

The 1922 election saw some Republican losses in Congress but they held both houses of Congress. This election also saw the formation of a cohesive Farm Bloc that would bedevil Coolidge when his turn came. Fordney and McCumber, authors of the tariff, lost their seats but the issue would remain. The Bloc tended to be progressive although it included members of both parties.

In 1923, the first hints of scandals to follow appeared. On February 1, 1923, the counsel for the Veterans Bureau resigned. On February 12, the Senate announced an investigation. Three days later, Director Charles Forbes resigned. He could not account for hundreds of millions of dollars of supplies and equipment. It became clear he had been selling them. When Harding learned of the scandal, he demanded Forbes resign but allowed him to leave the country. Soon after this Albert Fall resigned and took a job with Harry Sinclair‘s oil company. On March 14, Cramer, the counsel who had already resigned from the Veterans Bureau, shot himself. One of Daugherty’s assistants was confronted by Harding about accusations of corruption and the assistant shot himself on May 29. The Senate attempted to impeach Daugherty in 1922 but he was acquitted. Harding was quoted as saying ““I have no trouble with my enemies. I can take care of my enemies in a fight. But my friends, my goddamned friends, they’re the ones who keep me walking the floor at nights!”

The Harding party left for a two month “Voyage of Understanding” in June 1923. At this point, Coolidge was considering retiring from politics as he realized that Harding had most likely decided to drop him from the ticket in 1924. Everything changed on Friday, August 2 at 7:32 pm in San Francisco when Harding died.

To be continued here