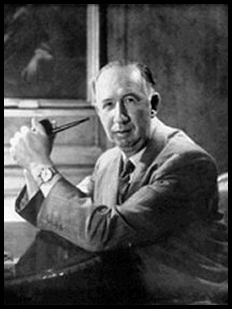

One of my favorite novelists is Neville Shute. He was an engineer, and so was I, plus he writes about people with an ability to show their humanity and their deeper motivations without a lot of explanation. He is the engineer’s novelist, the businessman’s novelist and should be on every list of conservative novelists. I have read all his post-war novels, most of his wartime novels and a selection of his pre-war novels. He died in 1960 and all his books are still in print.

I was a college student when “On the Beach,” possibly his most famous novel, came out. It scared me so badly that I have not been able to enjoy rereading it, as I have his other books. I was a college sophomore and familiar with his other work at the time. I had read his aviation novel, “No Highway,” and was aware that the plot device in that book, of metal fatigue causing a new airplane to crash without explanation, had been prophetic. Shortly after “No Highway” had come out, the British Comet jet airliners had begun to crash and, when finally identified, the cause was metal fatigue.

Shute had written another prophetic novel in the late 1930s, called “Ordeal,” which predicted the effects of the Blitz on London. Both of these books, with their predictions borne out by history, caused me to be very shaken by “On the Beach.” A rather successful movie was later made from this novel, which Shute hated because it had suggested that the two principle characters, played by Gregory Peck and Ava Gardner, had slept together while he believed it important to establish their morality, even when doomed.

I very nearly dropped out of school after that book and spent a year or two getting over the idea that I would soon be fried in a nuclear war. My reaction was based as much on my regard for his novels as for the topic, itself. A quite good movie was made from “No Highway” with James Stewart, Glynnis Johns, and Marlena Dietrich.

It was about this time that Shute became disgusted with Socialist England and emigrated to Australia. His conservative politics can be discerned in the rest of his work from this time. The most overtly political of his books is “In the Wet,” an attempt at prediction of the future. He attempts to look into the future, writing a novel set 30 years in the future and looking back through dream sequences, a device he uses rather often. He is too pessimistic about England, failing to anticipate Margaret Thatcher, and too optimistic about Australia, imagining that his adopted homeland has devised a weighted ballot system, which credits those with achievement more weight in voting. The book was written in the 50s and tried to predict the 80s. Shute died in 1960 and had no chance to update his predictions.

His autobiography, “Slide Rule” explains some of his political evolution as he recounts the story of the R 100 and R 101 competition. At the time, Shute (Norway) was working as an engineer for Geoffrey DeHavilland and Vickers aircraft company, which were building the R 100. The government had decided on a competition between the R 101 government sponsored project and the R 100 private project. From Wikipedia, with a bit of revisionism on the part of the web site, not known as a conservative stronghold:

R101 was the result of a British government initiative to develop airships. In 1924 the Imperial Airship Scheme was proposed as a way to provide passenger and mail transport from Britain to the most distant parts of the British Empire, including India, Australia and Canada and intermediate destinations. The distances were too great for conventional aircraft of the period. The specification called for airships with a passenger capacity of 150 including luggage, plus mails, in addition to the crew of around 40. In wartime the airships would be used to carry 200 troops or five fighter aircraft. This was expected to require airships of eight million cubic feet (230,000 m³) — well beyond then-current designs. As a result the two prototype airships of five million cubic feet (140,000 m³) were authorised; each to exploit competition and develop new ideas. Two teams were used: one, under direction of the Government Air Ministry, would build R101 (hence the nickname “the Socialist Airship”), and the other, a private company, Vickers, would build R100 (the “Capitalist Airship”) under contract for a fixed price.

Among Vickers’ engineers were the designer Barnes Wallis, later famous for the bouncing bomb and, as Chief Calculator (that is, Stress Engineer), Nevil Shute Norway, later well known as a novelist.

The story of the designs of R100 and R101, and the competition between them, is told in Shute’s Slide Rule: Autobiography of an Engineer, which was first published in 1954, and in Airship Saga, published in 1980 by Lord Venty. Shute’s book characterised R100 as a pragmatic and conservative design, and R101 as grandiose and over-ambitious. In fact the purpose of having two design teams was precisely to test different approaches, with R101 deliberately intended to extend the limits of existing technology. Shute later admitted that many of his criticisms of the R101 team were unjustified, and that he had been piqued by the scrapping of R100 following the crash of R101.[citation needed]

I’ll say that a “citation ” is needed! There is no sign that Shute Norway ever revised his opinion. In fact, one of his stories from Slide Rule is how Lord Nuffield, a rich auto manufacturer, decided to stop building the small gasoline engines that so much of the aircraft industry depended upon for smaller planes and trainers. Nuffield had finally had enough of the Air Ministry bureaucrats’ idiocy.

There are several transitional novels as he learns about his new country. “The Far Country” is one and holds up well. The English girl, a doctor’s daughter, comes to visit relatives in Australia who have been pitied a bit by the English branch of the family when it is quickly apparent to her that they have prospered far beyond the imagination of the English who stayed behind and who are now poor. An Austrian doctor is an immigrant who works as a lumberman. Australia is seen as the land of opportunity while England stagnates in a socialist muddle. The widow of an Indian bureaucrat, and the girl’s grandmother, starves to death in England, too proud to ask for help. The Australian couple married after World War I much against the wishes of the wife’s family. The only support they received from the family came from Aunt Ethel, who is now quietly starving to death in Socialist England. After the grandmother dies, the girl’s father, an overworked doctor in the NHS, reads the old lady’s letters and a recipe book that pictures a world incomprehensible to 1953 English girls. Cakes made with two pounds of butter, 18 weeks ration for one person. Steak and onions for dinner, a meal the doctor has not seen since before the war. It illustrates Shute’s point without the need for explanation.

“Requiem for a Wren” is another transitional book, and has a somber tone, as it deals with a young woman whose fiance is killed the week before D-Day as he is one of the special forces who cross the channel early to prepare the way. Shute knows a lot about this from his war work. The young woman eventually makes her way to Australia where she works as a maid for the parents of her dead fiance, never letting them know who she is. The brother of her fiance, who has been badly hurt as an RAF pilot, spends years looking for her, never realizing until too late that she was with his parents in Australia.

The “Rainbow and the Rose” is another transitional book, the story told in dream sequences, about a World War I fighter pilot who becomes an airline captain after World War II and eventually meets his daughter from a relationship of years ago. It begins in England and ends in Tasmania. All these transitional novels begin in England and end in Australia.

His classic book about Australia, “A Town Like Alice,” has been in print, especially in England, for 60 years. It is the story of a young English woman who was a prisoner of the Japanese in Malaya during World War II. She meets an Australian soldier, a POW, and has every reason to believe he is killed by the Japanese. She is repatriated but goes back to Malaya after the war to build a well for the simple people who sheltered her and her companions from the Japanese. Here again, is the theme that, given a legacy she did not expect, she goes back to help people who once were good to her. Once there, she learns that the Australian soldier survived. She goes on to Australia to see him and learn what has happened. In the meantime, he has learned she was not married (She was caring for an infant that was her employer’s) and has gone to London in search of her.

They meet and the rest of the story is about how her attempts at business, a shoe factory, a laundromat, a dress shop, transform the outback town into a pleasant place that is almost “A town like Alice.” Here again, Shute makes the business person a hero. Her small businesses employ local people, helping to keep girls near aging parents instead of their having to go thousands of miles away for work. Local stockmen cannot find wives and form families because the outback town has no amenities that would encourage a young woman to stay. As the local businesses that Jean Paget organizes begin to affect the town, there is a multiplier effect. This is one of the very few examples of economics and the multiplier effect in fiction. In the end, the town is transformed by business and becomes a thriving community.

Shute’s final novel, published after his death in 1960, is “Trustee From the Toolroom.” The story is of a man who lives in England, in Ealing where Shute himself grew up, and writes for a model engineering magazine. He designs and builds models which are described to readers with step by step instructions. In doing so, he has made friends all over the world. Friends who, when they learn he is in trouble, are willing to do what they can to help him. His sister and her husband, a retired naval officer, have decided to emigrate. They sail a small sailboat (Shute was a sailor) from England with the intention of settling in British Columbia. Because of severe currency controls at the time (A friend of my in-laws used to come for an annual visit and was dependent on them for expenses, an obligation she reciprocated when they visited England), they are unable to legally bring their funds to Canada so they smuggle diamonds in a box let into the keel with Keith’s help. They are lost in a southern hemisphere hurricane, with the yacht wedged into a coral reef surrounding an island in the Tuamotu Archipelago.

They have left their daughter with Keith and his wife until they send for her from Vancouver. Now, with the girl’s legacy lost in the south Pacific, Keith feels responsibility for the girl but the task is daunting.

Keith knows that the diamonds are there and accessible but only if he goes personally to retrieve them himself and in secrecy. The story of how he does this is one of the two or three best sailing novels of modern times. It also is a story of personal friendship and the honor of businessmen. The heroes are a mentally dull but competent seaman, a wealthy businessman and other characters who respond to a respected man who needs help. It is probably Shute’s most sentimental story. I have read it at least 50 times. It is probably a coincidence that most of the good people are Jewish but maybe not.

Probably his most mystical novel is “Round the Bend,” a story of a young man building an air transport business. Once again. the businessman is the hero. Along the way, he runs a business and undercuts his competition by employing local pilots and engineers, mostly Muslim since the business is set in the Middle East. About half way through the story, he meets a childhood friend, Connie Shaklin, a childhood friend from their early life working for an air circus. Connie comes back to Bahrain with Tom and helps him expand his business by expanding his ground engineer operation. Connie teaches the Muslim employees that every time they properly wire a nut to keep it from unscrewing, they are praying. He tells them the story of how Allah taught Mohammed that men should pray 50 times per day but allowed the requirement to remain at 5 times per day due to the weakness of men. Connie teaches his ground engineers, in a part of the world where native employees are notoriously unreliable, that they are praying by working to the best of their own ability. His methods are so successful that other airlines adopt them and he becomes a cult figure among ground engineers and their supervisors across Asia. He is consulted by imams and becomes a figure of reverence.

Inevitably, the British bureaucracy becomes alarmed and finally drives Connie from the Middle East. This results in severe consequences for the British but Shute has small patience with minor British officialdom. In the end, Connie becomes a Christ-like figure and Shute has written his most mystical novel. It is all based on plausible scenarios and the issue is left one of speculation but it is one of my favorite two or three of his books.

A review– A story which grips and fascinates, a story enriched by the observation and understanding which have made Shute’s work outstanding Scotsman He holds attention to the last page — Daily Telegraph

So convincingly does Shute tell the story and so cleverly does he leave the character of Shaklin deliberately vague that the book is as absorbing as anything he has written, and Cutter one of his finest creations

Glasgow Herald

There is a Neville Shute site, which is quite active and sponsors trips to locations of some of his novels. A recent entry shows how active it is.

I was recently contacted by the son of Forester Lindsley. Forester now lives in Brisbane, Australia. At 16, Forester joined Airspeed in York and moved with it to Portsmouth. Forester is now 90 and in poor health so I am interviewing him slowly. Apart from speaking to him, what is particularly exciting is that I have been told he has a large collection of photographs so I am hoping we will soon uncover some treasures. Forester worked on Cobham’s Air Circus planes and was a ground engineer on the first Ferry flights and was also involved in the aerial refuelling project. He met Amy Johnson several times and also said that he knew Flt Lt Colman, Airspeed’s test pilot, well. He spoke well of Shute and Tiltman. Forester worked as a Ground Engineer through the war and was working in Karachi in 1948 when Shute had his Proctor serviced there on his way through to Australia. Being a young ground engineer who joined aviation as a young boy, was involved with Cobham’s Air Circus, and later was working in The East where Shute met him, it is hard not to speculate that he must have been a partial model for the characters of either or both Tom Cutter or Connie Shak Lin in Round The Bend. Further speculation is encouraged by the story that Forester was doing a bit of Ground Engineer teaching in Karachi when Shute visited. Sadly when I tried to cross reference in the Flight Log for a mention of Forester I couldn’t find one but as the Flight Log is a hurriedly written diary this is not so surprising. I have been sent a lovely photo of a teenage Forester with an early version of the Airspeed Courier. He looks like a fun loving and likeable teenager just like Tom and Connie. Hopefully there will be more forthcoming as I hear more from Forester.

If you have read Round the Bend, you know exactly what the comment is about. There are thousands of people all over the world who know the novels well enough to immediately recognize the significance of the comment. They are like a treasure hunt of gems of writing and history. He is my image of the conservative novelist and should be read by engineers, conservatives and those interested in well drawn personal images.