An interesting piece in New York magazine describes the opinions of the man who wrote the book, The Big Short.

He is not optimistic.

Dodd-Frank really worked, and they kind of disagreed with the end of the movie, which implies that this is all going to happen again.

It sort of worked. One thing it has not changed is the sheer size of these institutions, they’ve gotten bigger rather than smaller. And I don’t understand that , I would have thought that from Too Big To Fail we would have found a way to make them small enough so that it was ok for them to fail. And know there’s all this complicated language about how you can resolve them in bankruptcy but I don’t believe it, and the markets don’t believe it. The bigger thing is — I regarded this crisis at bottom as a problem of incentives. People behaved badly because they were incentivized to behave badly, and the incentives haven’t really changed that much.

No, they haven’t and ZIRP is one reason. ZIRP is “Zero Interest Rate Program.”

I think they should have broken up the banks.

And in your opinion, why didn’t that happen?

It didn’t happen because the Obama administration decided that it was worse than the course of action they took. They considered it, kind of. If you asked Tim Geithner why it didn’t happen, he would say how am I going to do that? I am going to have to nationalize these banks, and then break them up. Well, we’re really not equipped to run the entire financial system out of the Treasury. And the system is in such disarray and chaos that we are more likely to create more crisis, than resolve the crisis if we do that. Which is not a terrible argument.

Geithner is, of course, the villain of Sheila Bair’s book, “Bull by the Horns.” My review of her book points out this statement.

Her tenure was stress filled and some of that stress came from the actions of soon-to-be Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner. The story opens in the crisis of late 2008 when the TARP legislation was first defeated by the House, then finally passed. She notes that the purpose proposed for the bill was immediately abandoned after it was signed. It was supposed to fund purchase of the toxic assets held by banks and by investors but quickly became a bailout for the big banks, judged too big to fail. Much of her time was spent fending off Geithner as he seemed to be obsessed with the welfare of CITIBank, a huge and weak international player. She is very critical of his efforts and of the CITIBank management.

Soon after this he became Treasury Secretary for Obama. Like a lot of people, he was thinking this.

Another kind of reform, which would eventually cause them to shrink a lot, would be vastly increasing the capital requirements, which has been floated by people, require them to hold not just about 7 percent or 6 percent but 20 percent, and what happens is they’d become a lot less profitable, they can’t take big big bets and no one would want to invest in them or work for them. But that has been roundly defeated at the regulatory level. I think, beneath that, the bigger problem is, virtually everybody at the table, even well-meaning government employees, when they are talking about what to do about these places, have — even if they aren’t thinking about it consciously, cannot help but consider the likelihood that the way they are going to make a living, a very good living, when they get done with government work, is to go work for one of these places.

That is called Moral Hazard and it has defeated any attempt at reform. And it may now be too late to fix it.

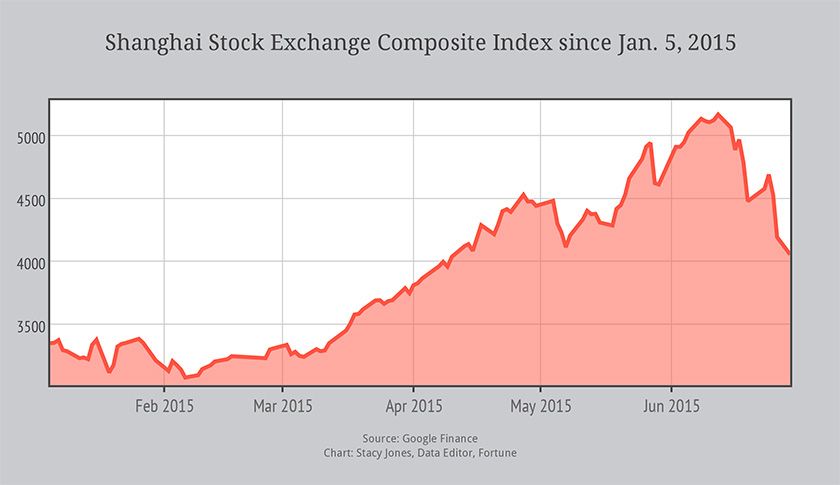

Analysts also point to concerns over Chinese market regulators, who they believe do not appear to have a good grasp of the market, even with the introduction of the circuit breakers. In an attempt to stabilize markets, China’s securities regulator has issued new rules to restrict the number of shares major shareholders in listed companies can sell every three months to 1 percent.

Marc Ostwald, a strategist at ADM Investor Services, believes that Soros’ comments — alongside a gloomy report Wednesday from the World Bank — only serve to cast a “long shadow” over global markets.

“It should be noted that the current turmoil distinguishes itself from 2008, when reckless lending, willful blindness to a mountain of credit sector risks and feckless and irresponsible regulation and supervision of markets were the causes of the crash, given that central bank policies have been encouraged and been wholly responsible for the current protracted bout of gross capital misallocation,” he said in a morning note.

Why is this different from 2008 ? It isn’t.

people didn’t want to know there was a bubble in the housing market, even though everyone knew something bad was going on.

It was really true, I remember coming across this phenomenon, on the wrong side of things: People were just thinking, “This doesn’t have to last very long for me to do well. And if it all goes down it’s not going to affect me. So why think about it too much?” There’s a great line in the movie: “You tell me the difference between corrupt and stupid and I’ll have my wife’s brother arrested.”

This explanation is still relevant.

For five years, Li’s formula, known as a Gaussian copula function, looked like an unambiguously positive breakthrough, a piece of financial technology that allowed hugely complex risks to be modeled with more ease and accuracy than ever before. With his brilliant spark of mathematical legerdemain, Li made it possible for traders to sell vast quantities of new securities, expanding financial markets to unimaginable levels.

His method was adopted by everybody from bond investors and Wall Street banks to ratings agencies and regulators. And it became so deeply entrenched—and was making people so much money—that warnings about its limitations were largely ignored.

Then the model fell apart. Cracks started appearing early on, when financial markets began behaving in ways that users of Li’s formula hadn’t expected. The cracks became full-fledged canyons in 2008—when ruptures in the financial system’s foundation swallowed up trillions of dollars and put the survival of the global banking system in serious peril.

That was part of it. The rest was the corrupt bargain that Democrats had with lobby groups for minorities.

I wrote about this in 2008 as it was happening.

Things did not begin to heat up again until the end of the Clinton Administration. The internet stock bubble left a lot of people with money to invest but few good opportunities. Many had taken their money out of the stock market after making plenty of money. Secondly, after 9/11, the Bush Administration was determined to avoid a recession brought on by the huge capital loss of the WTC collapse. The Panic of 1907 was precipitated by the San Francisco Earthquake and the huge losses to insurance companies. The Great Depression was partly a reaction to the default of war loans from World War I and the reparations demanded of Germany. There was fear that another severe financial panic would follow 9/11. In fact, that may have been a large part of the plan by Osama bin Laden. As a result, the banks had a lot of money to lend and they soon ran out of worthy borrowers. What to do ? Lend it to people with less than sterling credit. After all, houses were going to keep going up in price, weren’t they ?

Enter the chislers and scammers. Some of whom were former Clinton Administration members who got themselves appointed to the boards of the two big mortgage lenders. Did they have a broad background in mortgage banking ? No. They were politicians, like Jim Johnson who recently left the Obama campaign where he had been serving as the co-chair to vet potential VP nominees. What was his background ? Politics, not finance.

James A. Johnson is a United States Democratic Party political figure. He was the campaign manager for Walter Mondale’s failed 1984 presidential bid and chaired the vice presidential selection process for the presidential campaign of John Kerry. In the 2008 election, he is a member of the vice-presidential selection process for the presumptive Democratic nominee, Senator Barack Obama.

From 1991 to 1998, he served as chairman and chief executive officer of the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), the quasi-public organization that guarantees mortgages for millions of American homeowners. Previously, he was vice chairman of Fannie Mae (1990-1991) and a managing director with Lehman Brothers (1985-1990).

The rest is history but much of it is at that link.