Coolidge believed that the wedding of government and business would lead to socialism, communism or fascism. Hoover considered Henry Wallace a fascist for supporting the McNary-Haugen bill. Hoover, ironically, was to bring on the Depression by progressive measures that might have been called a form of fascism. The farm bill would be re-introduced under Hoover and die. Only during the New Deal would it find enough support to become law. The summer of 1927 was peaceful and prosperous. It was the summer of Babe Ruth’s 60 home runs. The Yankees would win the World Series and end up with a winning percentage of 0.714, still unsurpassed. In September, Gene Tunney defeated Jack Dempsey in the fight marked by the “long count.” The “Jazz Singer” came out that fall, the first talking feature picture. Charles Lindbergh flew the Atlantic in May of 1927. He and Coolidge were much alike yet different. Both were shy and diffident but Lindbergh was happy to cash in on his fame while Coolidge refused all offers after he left office.

Coolidge arranged for Lindbergh to return to the states aboard a US cruiser, Memphis, where he was met by a crowd and by cabinet members, then there was a huge parade through New York City. Lindbergh and his mother stayed with the Coolidges at the temporary White House where Dwight Morrow, close friend of Coolidge from Amherst, introduced the young aviator to his daughter Ann. Aviation stocks, along with many others, soared and the Dow Jones Average by year end was at 200, the record high.

In his December 6, 1927 State of the Union message, he mentioned an economic slowdown and asked for the same things he had been requesting; sell Muscle Shoals, help farm cooperatives and keep spending down. In May of 1928, he complained to reporters about Congressional spending. “I am a good deal disturbed at the number of proposals that are being made for the expenditure of money. The number and the amount is becoming appalling.” He managed to get another tax cut passed including a cut in the corporate tax rate. The surplus that year was $398 million.

Foreign affairs were never a big concern to Coolidge but the matter of war debts and reparations were and eventually would have a large hand in the coming collapse. Coolidge said in 1926, “Every dollar that we have advanced to these countries they have promised to repay with interest. Our National Treasury is not in the banking business. We did not make these loans as a banking enterprise.” He is supposed to have said, “They hired the money, didn’t they ?” but in fact he never said that. He did say, “Unless money that is borrowed is repaid, credit cannot be secured in time of necessity.”

The high tariffs were a major barrier to repayment of these debts as Europeans could not sell enough to the US to balance trade. The US accumulated massive gold reserves in the 20s and the central bankers tried to avoid a situation where the US had all the gold in the world. This led to very low interest rates and an aggressive policy of loaning money to countries with questionable credit ratings, especially in Latin America. The low interest rates led to a bubble and, after 1928, the collapse was inevitable. JP Morgan and other Wall Street banks supported lowered tariffs and free trade, at least in a relative sense. Coolidge’s greatest mistake was in continuing those tariff rates but that was Republican policy. The tariff was bringing in money that would retire the national debt. Only later was the folly seen in high tariffs.

Harding had allowed renegotiation of UK debt and Coolidge went even farther with Italy, France and Belgium. He supported the Dawes Plan, which provided loans to Germany so they could repay the UK and France. The money went in a circle but nobody seemed to notice that. He encouraged loans to German industry and Ferdinand Eberstadt, a Dillon Read banker, commented, “We have the iron, coal and steel industry, the United Steel Works, which is approximately the size of Bethlehem Steel and second only to United States Steel…” The loans were arranged through JP Morgan and Company with State Department blessings. In 1942, Ferdinand Eberstadt was asked to take over as Chairman of the Army and Navy Munitions Board and Vice Chairman of the War Productions Board. He came up with a system of priorities called the” Controlled Materials Plan”, which revolutionized the handling of raw materials and unlocked a potentially fatal deadlock in the flow of raw materials to war industries. The loans to Germany did not do as well.

Coolidge supported the Merchant Marine and, after the Jones Act of 1928, ship construction. He supported the St Lawrence Seaway project which would bring international shipping to Chicago and other inland ports of the US and Canada. He was a great supporter of international business relationships. In 1925 he said, “Americans have over 20 million tons of merchant shipping to carry the commerce of the world, worth $3 billion.” He also said, referring to World War I, ” We fought not because Germany invaded or threatened to invade America but because she struck at our commerce on the North Sea and denied to our citizens on the high seas the protection of our flag.” In his most aggressive statement, “An American child crying on the banks of the Yangtze a thousand miles from the coast can summon the ships of the American navy up that river to protect it from unjust assault.” The statement was not idle as there were threats to Americans in just that area.

Difficulties with Mexico, chiefly nationalization of oil fields and equipment, led to Coolidge sending his friend Dwight Morrow as ambassador. His instructions were simple; “Keep us out of war.” Morrow was highly successful, even negotiating a compromise between the Mexican president, Calles, and the Catholic Church. During this time, Charles Lindbergh visited, fell in love with Ann Morrow and married her. The 1927 Calles-Morrow agreement settled most issues amicably. As a result of the difficulties, however, American oil companies turned their attention to Venezuela and the Middle East. Mexico lost badly as a result of the ill-advised nationalization attempt. In 1938, the new Mexican president returned to confiscation and the Roosevelt administration handled this with far less success. Nicaragua, which the Marines had occupied since 1912, and China posed serious foreign policy issues for Coolidge but he tried to keep out of trouble and even approved another Washington Naval Conference, which opened in 1927 but which found no success. After that failure, the US Navy began building ships again. The 1924 conference at least gave us two of our big aircraft carriers for World War II as two battle cruisers were converted to aircraft carriers, the Saratoga and the Lexington (which was sunk in the Battle of the Coral Sea).

The Kellogg-Briand Pact, which would outlaw war, was passed by the Senate 85 to 1. Ultimately, 62 nations signed. It was the height of the rejection of the horrors of World War I. Coolidge signed it on January 17, 1929. The last year was tranquil. Walter Lippmann wrote, “During the last four years the actual prosperity of the people combined with the greater enlightenment of the industrial leaders, has removed from politics all serious economic causes of agitation.” There were other, less sanguine views. Ludwig von Mises and Frederick Hayek were writing that the artificially low interest rates were setting up the world economy for a crisis.

There were warnings in America. William Z Ripley, a Harvard economist, warned that business leaders were too independent and approximated the “robber barons” of the 19th century. An article of his in The Atlantic Monthly brought him to Coolidge’s attention and they had a meeting. He criticized inaccurate financial statements and the separation of ownership and management. He was correct about the first but his complaints about management were largely out of date as the era of the professional manager was arriving. He was railing about the great wave of incorporation and amalgamation of American business that was inevitable as family owned businesses gave way to professionally managed corporations. Walter Lippmann wrote, “The new executive has learned a great deal that his predecessor would have thought was tommyrot. His attitude toward labor, toward the public, toward his customers and his stockholders is different. His behavior is different….He does not arouse the old antagonism, the old bitter-end fury, the old feeling that he has to be clubbed into a sense of public responsibility. He will listen to an argument where formerly he was deaf to an agitation.” After 1929, Ripley was credited with predicting the crash and depression but his complaints were largely about modern business practices. He missed the causes and did not sound the correct warning.

Coolidge’s response to Ripley’s warning about speculation and inadequate disclosure in financial statements was to agree but he replied that those were matters that were New York state’s responsibility. Years later, Ripley wrote a letter to William Allen White and agreed with Coolidge that, in those days before the Securities and Exchange Commission, Coolidge was right. Ripley was correct that speculation was behind the huge bull market, although that was mostly true after 1928, but no one suggested the solution might be to raise interest rates to deflate the bubble. Before 1928, the bull market, like that during the Clinton administration, was driven by technology and rising incomes.

The real speculation boom took off after Ripley’s meeting with Coolidge, probably in mid-1927, and in April 1928 the Dow Jones Industrials stood at 200. Railroads, about which Ripley particularly complained, were at just over 120. By the end of the boom of 1929, Industrials were at 381.17, almost doubling in one year. Who were the men who might have acted to stem the tide of rampant speculation after 1928 ? Governor Al Smith turned over the office to Franklin D Roosevelt, who would preside over the 1929 crash as governor. Coolidge has widely been considered ignorant about economics but in fact he was quite sophisticated. He made recommendations for investment to his father that were excellent, for example in trolley car lines in an era when great fortunes were made in that field. The great Henry Huntington fortune in California was made in trolley car lines.

Some of Coolidge’s political advisors, like RNC Chair Butler, began to prepare for a 1928 campaign. In July, 1927, Coolidge told his secretary Sanders that he did not plan to run in 1928. Sanders’ reply was, “I think the people will be disappointed.” Coolidge told him that ten years was too long for a president to stay in office. He handed Sanders a slip of paper on which he had written “I do not choose to run for president in 1928.” That sentence has been analyzed by political science types for the past 80 years. Did he want to be drafted ? Probably not. A press conference was scheduled for August 2, the fourth anniversary of his presidency. Sanders suggested Coolidge wait to make his announcement. At the press conference, a reporter asked him to talk about his most important accomplishments. His response was low key, “It is rather difficult for me to pick out one thing above another to designate what is called here the chief accomplishments of the four years of my administration. The country has been at peace during that time. It hasn’t had any marked commercial or financial depression. Some parts of it naturally have been better off than other people, but on the whole it has been a time of a fair degree of prosperity.”

At 11 AM that day, Coolidge gave his declaration to Sanders and asked him to have it printed on sheets of paper, with enough copies for the reporters. They then called the reporters in and Coolidge, mildly amused, handed them individually to each reporter, not permitting any to leave the room until all had a copy. They then rushed for the telephones. Later that day, Senator Capper saw Mrs Coolidge and commented on the surprise, “That was quite a surprise the president gave us this morning.” She replied, “Isn’t that just like the man ! He never gave me the slightest intimation of his intentions ! I had no idea!” We may doubt that she had no idea but it was just like the man. The stock market fell on the news for several days but eventually regained momentum as it went on to new highs. Some said that the market began to believe he would accept a draft. The speculation continues to this day among the few historians who still think about Coolidge. Why did he decide not to run ?

In his Autobiography, he repeats his statement about ten years being too long for a president to serve. Another reason might have been his modesty, “It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion. They are always surrounded by worshippers. They are constantly, and for the most part sincerely, assured of their greatness. They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation which sooner or later impairs their judgement. They are in grave danger of becoming careless and arrogant.” He had no doubts that he had made the right decision. Others speculated that young Calvin’s death had taken the glory and the work was grinding him down. Mrs Coolidge later offered another explanation after her husband’s death. In a discussion with a former cabinet member, “that gentleman expressed his conviction that the president’s decision not to run again had been a wise one; that, not to mention other reasons, he felt the country would undergo the most serious economic and financial convulsion which had occurred since 1875…” A friend of hers later recalled her saying, “Poppa says there is a depression coming.” Most of these statements came years after the fact and may be suspected of hindsight.

One recollection may be reliable. White House secretary Edward Clark, writing in 1935, recalled Coolidge saying that he had been worried for a long time about the possibility of economic troubles. In 1927, just after naming Dwight Morrow as his special envoy to Mexico, Clark recalled him praising Morrow as the kind of person who should be in power in the event of a financial crisis. Clark asked, “Do you expect some sort of financial crisis?” Coolidge replied, “I do not attempt to predict anything but people do not seem to see that, while we in this country are increasing production enormously, other countries are closing their doors more and more against our products.” It is not clear if he realized that the protective tariffs he had supported were responsible for this. He continued, “Our foreign outlets are constantly diminishing.” He named the new USSR, an independent India, still 20 years away and China as future powers and potential danger spots.

After his announcement, Hoover came to see the president and asked about support if he chose to run. Coolidge was elliptical, as usual, in his answer. In May 1928, he came to him again and told him that, even though he had 400 delegate pledged to him, he would support Coolidge if he chose to run. Coolidge replied,” If you have 400 delegates, you better keep them.” Hoover added, “I could get no more out of him.”

What portents might have led to worries about the economy ? Financial news was not carried in daily newspapers then. Few knew what was going on outside the financial community. The return of the British pound to gold in 1925 was an omen. It was ill advised and Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, later called it the worst mistake of his career. It accelerated the rush of gold to the US Treasury and increased the urgency of the actions of Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Ben Strong, in his efforts to balance world economies. Low US interest rates and questionable bond issues followed much as questionable investments in mortgage backed securities would lead to trouble 80 years later. In mid 1927, the Fed lowered the rediscount rate from 4%, where it had been since 1922, to 3 1/2%. It also bought $500 million in open market operations, increasing the money supply. Broker loans to speculators responded. Coolidge was asked about this and responded that he had no power over the Fed. Strong was universally trusted but few knew that he required treatment for tuberculosis in a sanitarium recently.

In January 1928, the NYSE announced that broker loans had increased by $1 billion in 1927. Coolidge was asked about this and was noncommittal, saying that he was not an expert but that the number of shares and the bank deposits were much larger than in the past. A cousin of Coolidges’, who edited the New York Journal of Commerce, asked him about this some time later. Coolidge replied, “I should say that any loan made for the purpose of gambling in stocks was an ‘excessive’ loan.” Willis, the cousin, said he wished Coolidge had said that instead of what he had said. Coolidge asked why and Willis said, “Simply because I think it would have had a tremendous effect in repressing unwholesome speculation, with which I see you have no sympathy.” Coolidge replied that his personal feelings did not necessarily reflect his official statements that came from government policies.

Benjamin Strong

In 1928, recognizing the speculation that had followed the reduction in the rediscount rate, Strong raised it again, finally to 4 1/2 %. This was too late as speculators saw great profits ahead and ignored the interest rate. Strong died on October 16, 1928, almost exactly a year before the crash. Strong had had a role in the founding of the Federal Reserve and no one knew what he knew. He has been harshly criticized by the Austrian School of economists. Still, his loss at that moment was a critical one. In 1928, Coolidge and Mellon made no bullish statements. There were several corrections that year but each was followed by a new rally. Coolidge was asked about the rise in the rediscount rate and claimed ignorance of the workings of the Federal Reserve, a serious error if true.

At the Convention, a fiery nomination speech by Ralph Cole of Ohio, almost stampeded the delegates to Coolidge but the chair called for a roll call vote and Hoover was nominated on the first ballot. Coolidge made a few speeches in favor of Hoover during the campaign but mostly stayed out of sight. Historians now believe that had Coolidge been the candidate, he would have won with a larger total than Hoover. Al Smith lost the election, not because of his religion, but because of “Coolidge prosperity.”

Summing up

In 1982, a small book, published by the Carolina Academic Press, and written as a dissertation for a PhD in political science, was published. It is titled, “Coolidge and the Historians.” Copies are rare but it is almost indispensable as a place to start a study of Coolidge, at least after the “Autobiography.” The chapters each cover one aspect of the mistreatment of Coolidge by historians and several go into elaborate detail on the specifics. I will try to summarize. The Foreward is written by Harry V Jaffa.

1. Coolidge the man. Thomas Silver, the author, points out that the Republican presidents of the 1920s are considered by many historians as an interregnum between the Wilson Administration and the New Deal. Wilson, in spite of many failures, not least the Versailles Treaty, is considered a great president. Harding and Coolidge are considered failures. Certainly Harding did himself great harm in his choice of several cabinet members but no financial scandal has been connected with him. Unfortunately, he had a messy private life and this has denied him a fair hearing on his policies. I have tried to show that they were responsible for the quick recovery from a severe depression in 1919 to 1921. In fact, this was a more severe recession than that of 1929 to 1932. Coolidge inherited a country in which the three previous presidents had ended their terms in defeat, repudiation and death in spite of high hopes at the beginning.

A Pocket History of the United States describes Coolidge and Harding thusly, “concern for equality of opportunity would have come with better grace had the Harding and Coolidge Administrations shown a sincere and sustained interest in the welfare of labor and farmer groups. But these administrations were interested only in the ‘businessman’ and their conception of business was a narrow one. Neither the farmers nor the workingmen shared the piping prosperity of the twenties. There was a brief but short break in farm prices in 1921; by the mid-twenties a gradual decline set in and continued without interruption until the operation of the New Deal reforms became effective. Yet in the face of this situation the Harding and Coolidge administrations, so eager to place the government at the disposal of business, evinced an attitude of indifference to the farming interests.” The authors describe him as, “A thoroughly limited politician, dour and unimaginative, thrifty of words and ideas, devoted to the maintenance of the status quo and morbidly suspicious of liberalism in any form.”

Samuel Elliot Morrison, author of the Oxford History of the American People, liked him no better. Coolidge, the second of three “inept” Republican presidents of the twenties was “mean, thin lipped, little, mediocre, parsimonious, not as bright as people thought, dour, unimaginative, abstemious, frugal, unpretentious, taciturn, an admirer of wealthy men, reactionary, a cynical doubter of the progressive movement, and democratic only by habit and not by conviction.” (Page 933 of 1965 edition) He took it easy in the White House with a long nap every afternoon. He maintained his feeble health by riding on a mechanical horse. The history ends with a pean to President Kennedy, including the score of the Camelot music.

The most devastating picture of Coolidge is in the Schlessinger book, “Crisis of the Old Order”. I read this as a teenager and am embarrassed to see how subjective it is, including falsities that are just indefensible. Schlessinger describes Coolidge’s career, “The Boston police strike gave him as governor an “accidental” reputation for swift decision and made him Vice-President. But he had little impact on Washington. According to a young Republican editor in Michigan, Arthur Vandenberg, “Coolidge was ‘so unimpressive’ that he would probably have been denied renomination.”

The story of the Boston police strike was not in swift decision by Coolidge but cool patience while the situation developed and then a courageous decision that he expected would end his political career. Arthur Vandenberg was later a US Senator and Schlessinger was very selective in his quote from the Senator as a young man. The full piece from which this incomplete sentence was selected goes as follows, “Death put its tragic hand upon President Harding before his work was done. Succeeding him came a quiet, modest, unperturbable New Englander who– while so unimpressive as Vice-President that he probably would have been denied renomination even for second place, had his chief survived– has captured the the well-nigh universal imagination of the people in his unruffled common sense dependabilities in the higher station which he now occupies in his own right. The character of President Calvin Coolidge partakes of the atmosphere of those granite hills that gave him birth…” It goes on in that vein, in contrast with the dishonest use of a fragmentary quote by Schlessinger. The good professor continues his use of the dishonest quote throughout his discussion of Coolidge, a practice which has recently been coined as “Dowdified” in “honor” of a NY Times columnist who uses the same practice. She, at least, is not considered a historian.

2. The Boston police strike. The treatment of this segment of Coolidge’s career has been negative since the 1930s. A biography of Coolidge still in print as part of a presidential biography series, likewise attributes his success to luck and writes that “He who had been the last in acting had become the first in receiving credit.” In fact, it was Coolidge’s support of police commissioner Curtis that brought on the strike and defeated Mayor Peters’ attempt at compromise with law breakers. The historian calls Coolidge’s support of Curtis “Passively at first and later through timid action..” There was no doubt about his firmness at the time and contemporary newspapers made that clear. Coolidge was always a man of his word while not always the first or the loudest to speak.

3. The McNary-Haugen bill. The accusations of the later historians have been that Harding and Coolidge were devoted to businessmen and ignored the plight of farmers. Secondly, that they were an example of Laisezz Faire capitalism. Another history text commonly used in college courses states, “It was well known that Coolidge held no brief for new or unconventional ideas. “The business of the United States is business,” he had said. (Not true as we have seen) “In a vague way this meant that business should be positively assisted by high tariffs and, in some cases by outright government subsidies, as well as by reduced taxes and a minimum of government regulations or interference. He positively opposed any government aid or support to agriculture and labor… The president emphatically stated his position on agricultural problems in his first annual message…, Senator Pat Harrison wryly remarked that the section of the president’s message he liked the best was where he told the farmers to go to hell.”

The untruths or distortions include the fact that no direct subsidy to business was ever proposed by Harding or Coolidge. There were some residual programs left over from Wilson and the war. Tax reductions for business could be compared with the fact that farmers generally paid much lower tax rates than business. High tariffs were not unique to business, as we have seen.

4. The Mellon-Coolidge tax cuts When President Kennedy proposed tax cuts in the 1960s, his action was widely approved by most Democratic economists. John Kenneth Gailbraith did dissent and put the matter as a quote from a businessman. “‘I can’t get it through my head,’ said the President of International Harvester in Chicago the other day, ‘how you can get more money by cutting revenue.'” Professor Gailbraith probably did not correct the man’s economic ignorance by pointing out that tax rates and revenue were not the same thing. The New Republic, however did publish an article in support of Kennedy’s proposal pointing out that revenue rose each year in the Coolidge administration as tax rates were cut three times. They did not refer to the articles they had published in the 1920s attacking those tax cuts.

5. The Coolidge Prosperity and the Great Depression- connected ? That would seem odd but it has been the conclusion of many prominent historians. Professor Hicks, in his history of the era, writes, in the twenties, the Republicans “handed over the nation to business leadership, the Presidency along with the rest. But business leadership led straight to the panic of 1929.” Nevins and Commager write, “concentration of wealth and power in many great corporations produced a national economy fundamentally unhealthy.” Schlessinger, “seeing all problems from the viewpoint of business,… had mistaken the class interest for the national interest. The result was both class and national disaster.” The investor “class” was not mentioned by Schlessinger.

The author’s conclusion is that, in the case of Coolidge, history has been used as a weapon.

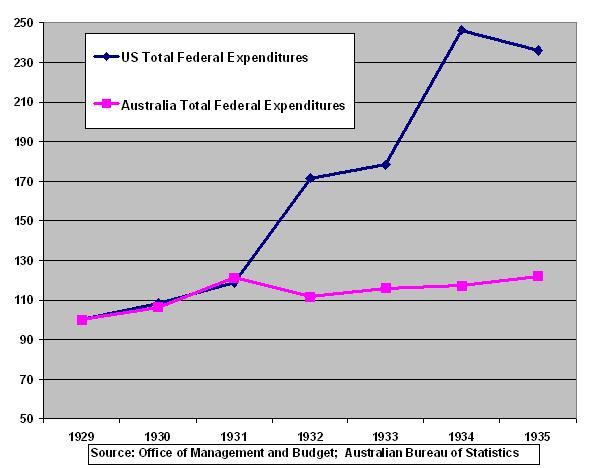

Based on my reading, I see Coolidge as the last president who did not turn to government as the response to any problem. Hoover was a progressive and there is no discernible difference between his policies and those of Roosevelt in his first two or three years. There have been objections that the federal government was much smaller and so Hoover’s attempts at stimulus were miniscule compared to Roosevelt, or especially those of Obama. That is true in a way but the dollar has depreciated so enormously since Coolidge that comparisons are difficult. An ounce of gold in 1924 was worth $20. It is now 80 times that, meaning the dollar is worth slightly more than one 1924 cent. Gross domestic product was much smaller, in real and in inflated dollars. But look at Hoover’s spending in graphic terms. Contrary to Paul Krugman, he doubled spending.

The Depression, in my opinion, was caused by several interlocking factors. One was the speculation born of interest rates that invited it, just as the near zero rates since 2000 brought the housing bubble and the 2008 collapse. Another was the use of high tariffs in a throw back to mercantilism in which each country, that thought it could, tried to beggar the others. Great Britain had shown in the 19th century that free trade was preferable but too many people forgot that. Hoover worsened things by signing the disastrous Smoot-Hawley tariff in spite of a letter from 1,000 economists begging him to veto it. Hoover tried to keep wages high with government action, exactly the wrong thing to do. Allowing businessmen the flexibility to lower wages to keep costs down would have avoided the high unemployment. Many of them might have survived, as well. Banks were poorly positioned to survive the crash because they were too dependent on local conditions. The FDIC, when set up under Roosevelt, was a great help but allowing bank branches would have reduced the vulnerability of the thousands of small local banks. Coolidge did not think he could intervene in stock speculation and one would think that the creation of the SEC would put a stop to this weakness. However, the SEC sat like the dog that did not bark in the night when mortgage backed securities and grossly fraudulent lending criteria brought the economy to the brink. Too many have forgotten, or never knew, the closeness of the Hoover and FDR policies during the period 1929 to 1937.

I’m sure you are all tired of my opinions by now, if not of Calvin Coolidge himself. I will stop here but list some books to read.

1. First is the Autobiography.

2. Next Robert Sobel’s biography

Those two are indispensable.

3. Coolidge and the Historians.

4. The High Tide of Conservatism 1924. The title is actually longer but this gives you the idea

5. Why Coolidge Matters. Less helpful but interesting.

6. The Forgotten Man. This is, of course, essential to understanding the Depression.

7. After the Fall by Nicole Gelinas, is excellent in explaining the 2008 crash.

Tags: economics, economy, election, financial, politics, Republicans

“Coolidge’s greatest mistake was in continuing those tariff rates…”

Sorry. Not sure I buy it. In any case, even if tariffs were too high in the 1920’s, I’m absolutely convinced that tariffs are too low in the 21st century.

America need to be re-industrialized – and that won’t happen until we “force” the issue via government policy.

YES! I’M CONTRADICTING MY GENERAL BELIEFS!

Nope, doc, you’ll get no “defense” from me other than pure pragmatism.

While it goes against all my instincts to propose that government limit individual economic opportunities regarding “saving money” via buy less expensive foreign made goods and nowadays (via the internet) services, I’m quite content to call for a short term limitation of individual economic liberty IN THIS ONE RESPECT as the price for saving the country in the long term.

In any case, we’re not talking “fair” trade in the sense of capitalist states trading with capitalist states. Instead, what we’re talking about is fascism/mercantilism vs. our own highly regulated crony capitalism.

(*SIGH*)

Oh, doc, there’s so much I’d change (or rather “restore”) if only I had the power… but I don’t have the power.

(*SHRUG*)

Therefore, as we work from within to “restore” America, I believe we need to “adjust” our trade and tax policies to reward re-industrialization and nationalism while discouraging the “internationalism” which is a large part of the ongoing assault upon traditional American values, hopes, and dreams.

Manufacturing is still very much a part of the economy and growing. One thing we can credit Obama with doing. The dollar is plunging and making exports cheap to the other countries. I used to go to Europe every year. No more.