Genetic engineering may have explained the mortality of the 1918 flu. Apparently, three genes are responsible for the viruses ability to infection lung and not just bronchus.

“We wanted to know why the 1918 flu caused severe pneumonia,” Kawaoka said in a statement.

They painstakingly substituted single genes from the 1918 virus into modern flu viruses and, one after another, they acted like garden-variety flu, infecting only the upper respiratory tract.

But a complex of three genes helped to make the virus live and reproduce deep in the lungs.

The three genes — called PA, PB1, and PB2 — along with a 1918 version of the nucleoprotein or NP gene, made modern seasonal flu kill ferrets in much the same way as the original 1918 flu, Kawaoka’s team found.

There was a second reason for the high mortality in 1918-1920. The principles of thoracic surgery, including the physiology of respiration were not understood at the time. Thousands of flu cases, those with pneumonia, developed a secondary bacterial pneumonia and then developed empyema. Empyema is a collection of infected fluid in the space between the lung and the chest wall. We now know how to treat this condition. The principles of treatment are here. Note the observation that Hippocrates understood the principle of empyema; namely that thin fluid in the collection could be drained by an opening in the chest wall but the patient would die. Hippocrates didn’t understand why. The knowledge of lung physiology would not come until the 19th century. However, Hippocrates did observe that draining thick pus through an opening in the chest did not result in the death of the patient in all cases, as it did in those where the fluid was thin and watery. What was the reason ?

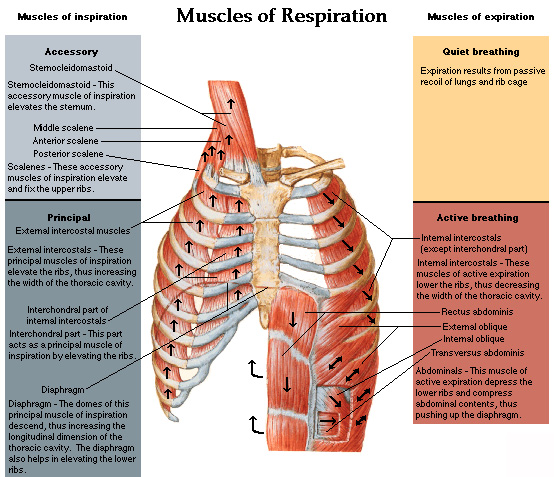

We now know that a relative vacuum exists between chest wall and lung. The chest wall is rigid and, during respiration, it changes its volume by using the “bucket handle effect” of the ribs.

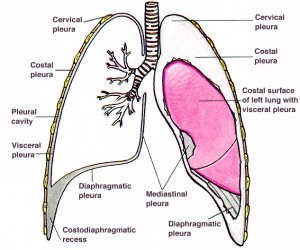

The space between lungs and chest wall is shown along with the general anatomy. That space is what fills with fluid in cases of pneumonia that develop empyema.

The ribs are curved and, when the muscles of the chest wall pull up on them, as shown by the arrows, the cross section of the chest cavity increases because of the “bucket handle” effect. With expiration, the ribs move back down and the volume of the chest cavity decreases. This volume shift, aided by the piston effect of the diaphragm, moves air in and out of the chest. The lungs are not attached to the chest wall, allowing them to slide up and down and accommodate their shape to the shape of the chest wall. If there is a hole in the chest wall, the air can move into the space between the lung and chest wall, collapsing the lung. This is called a “sucking chest wound” in trauma care. If the hole in the chest wall is larger than the trachea, air will move more easily in and out of the chest and respiration through the trachea will stop. This was the great barrier to chest surgery that was not overcome until the 1920s. The flu epidemic, and the research into the cause of death in so many cases, led to the understanding of how the chest works.

I recently reviewed a book about the history of the 1918 flu epidemic and, because it ignored the issue of empyema, I could not finish it. They had only half the story. The story of empyema, and the cause and cure, resulted from work of the Empyema Commission, chaired by Evarts Graham, professor of surgery at Washington University of St Louis medical school. Here is one of many scholarly works describing his great accomplishment. Unfortunately, little of this has penetrated the general history of the epidemic in spite of 90 years. In a recent article about the military cases during the First World War, it states: During World War I, the overall empyema mortality rate among US military forces was 61%. The same, or greater, mortality was seen in the flu cases that occurred in the same period. Untreated empyema was virtually 100% fatal.

During World War I, empyema treated by thoracotomy was associated with a mortality of > 30%. This prompted the establishment of the Empyema Commission, which recommended chest tube drainage for treatment.

The surgeons who were treating the flu cases, just as those treating empyema due to war wounds, used the old Hippocratic treatment of draining the pus from the empyema. Note that in the war wound cases, 70% of these patients survived. The flu cases were different and almost all died in a few hours after the fluid was drained. The difference was that the empyema in flu cases was due to streptococcus infection, which produces a thin fluid and does not cause the lung to stick to the chest wall. When the chest was opened, the lung collapsed and these already sick patients succumbed. Hippocrates had predicted this. The war wound cases did better because the staph infections of the pre-antibiotic days (“Laudable pus”) caused the lung to stick to the chest wall and it would not collapse.

Eventually, Graham learned that using a tube instead of an open hole to drain the pus, and placing the chest tube under water at its lower end, would seal the air leak but allow drainage of the pus. His work opened the door to thoracic surgery and, today, would save most of the cases in a new flu epidemic. Graham was also the first to warn of the association between smoking and lung cancer, a disease he was to die of 1957. He performed the first successful removal of a lung for cancer and his patient attended his funeral 24 years later.

Genetics is a powerful tool in the treatment of disease but physiology is still as important. Scientists understand the first but may not be aware of the other factors. There is no substitute for the experience of treating patients.

Fascinating story Dr. Kennedy. Your descriptions, not only of knowledge, but how it is acquired, are exceptional.

Thanks. I get frustrated when monumental advances are just ignored because the concept is hard to understand. I have a chapter on this in my book. The real solution to thoracic surgery was the invention of the cuffed endotracheal tube. That allowed inflation of the lungs with the chest open. That invention came in the 1920s. Before that, if you opened the chest, the lungs collapsed and the patient died. There was even a sealed room used for a while for chest surgery. The patient’s head stuck out a hole in the side and the pressure in the room was lowered. That was used for a few years, especially in Germany where it was invented. The other people in the chamber could breathe OK but it was very expensive to build one big enough for an operating room.

Some of the story is here.

Another great post, Dr. Capt. Mike K.!

And a Happy New Year to all!!

Same to you. I got so busy this week, I never got the time to call Joe S. Maybe next week. I’m going to the geriatric society meeting in April-May in Chicago. Maybe you should go. Geriatrics is going to be big the next ten years. Be a fun trip.

The other part, Dr. K., is that Kuhn business about paradigm change. “New” medical techniques aren’t referenced using “old” data.

I understand that a lot of physicians knew that antibiotic treatment could cure peptic ulcers in the 1950s. But it was not possible for bacteria to survive in the stomach (wrong on several levels, actually).

A fascinating read, Dr. K.

And yes, gerontology will be a big, big area of research. People aren’t excited right now by the results with nematodes and fruit flies. Folks I know are moving into mice. THAT will get people’s attention.

And granting agencies? As the “deciders” get older, I predict a deep and well funded investigation into this area.

Sort of how the discoverers of Viagra (well, the side effect of NO, anyway) won a Nobel Prize.

There are a number of similar stories about treatments that were ignored. The most obvious was, of course, the relationship between water and cholera that took many years to establish. Florence Nightingale and John Snow have a chapter in my book. Then came lithium for depression. There was no drug company to push it and it took decades for that to be accepted. It was actually being used by psychiatrists when it was illegal, in a sort of civil disobedience campaign. Then, of course, in my own time in practice, the peptic ulcer thing became known. The reason we have gastric acid is to sterilize food but nobody thought of an acid loving organism. Now, we are going through the same thing with Archea.

Helicobacter pylori is a fascinating organism, Dr. K. You should look at Martin Blaser’s articles on its relationship to humanity—it maybe that it is really a commensal organism that occasionally goes bad.

H. pylori secretes urease, so essentially is is surrounded by a “buffer zone” of ammonia that protects it from the stomach acid. And it burrows into the gastic mucosal region as well.

It turns out that many enteric bacteria have a whole suite of genes turned on in response to stomach acid. It makes sense, since the major route by which intestinal inhabitants gain access to the GI tract is oral! So those organisms must survive passage.