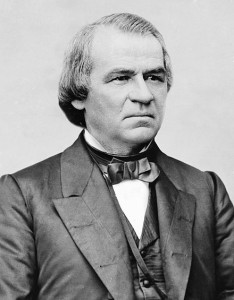

I think I see some similarities between the Democrats’ apparent efforts to try to impeach President Trump and the impeachment of Andrew Johnson in 1868.

Andrew Johnson was a “war Democrat,” meaning that he was a Democrat who supported the Union. He was Governor of the border state of Tennessee. Lincoln considered the border states critical in saving the Union.

“I hope to have God on my side,” Abraham Lincoln is reported to have said early in the war, “but I must have Kentucky.” Unlike most of his contemporaries, Lincoln hesitated to invoke divine sanction of human causes, but his wry comment unerringly acknowledged the critical importance of the border states to the Union cause. Following the attack on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for troops in April 1861, public opinion in Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri was sharply divided and these states’ ultimate allegiance uncertain. The residents of the border were torn between their close cultural ties with the South, on the one hand, and their long tradition of Unionism and political moderation on the other.

In 1864, after Atlanta was taken by Sherman, Lincoln began to think about the situation after the war. He met with Sherman and Grant on March 28, 1865. He had two weeks to live. He talked to them about his plans for after the war ended. Sherman later described the conversation. Lincoln was ready for the post-war period and he told Sherman to assure the Confederate Governor of North Carolina that as soon as the army laid down its arms, all citizens would have their rights restored and the state government would resume civil measures de facto until Congress could make permanent arrangement.

In choosing Johnson as his VP in 1964, Lincoln was doing two things, he was supporting his argument that no state could secede from the Union. The radical Republicans like Stevens and Sumner had taken the position that states had “committed suicide” by seceding. There was even a movement at the Baltimore Convention to nominate someone else, like Fremont who had been the nominee in 1856. The other was allowing the Convention to choose the VP nominee. It did seat some delegations from states, like Tennessee, that were still the scene of fighting. Only South Carolina was excluded.

The Convention was actually assumed to be safe for a Hannibal Hamlin renomination. Instead it voted for Johnson by a large margin. The final ballot results were 494 for Johnson, 9 for Hamlin. Noah Brooks, a Lincoln intimate, later recounted a conversation in which Lincoln told him that there might be an advantage in having a War Democrat as VP. Others, including Ward Hill Lamon, later agreed that Lincoln preferred a border state nominee for VP.

An so, Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat, was elected to an office that no one ever considered as likely to become President. No one anticipated Lincoln’s assassination. However there was a significant segment of radical Republicans that wanted to punish the states that had seceded and those who had joined the Confederacy, contrary to Lincoln’s plans. He had intended to restore the local governments, pending Congressional action to restructure the state governments. The Convention was well before Atlanta fell to Sherman’s army and Lincoln was not convinced he would be re-elected. The War Democrat VP nominee would help with border states.

Johnson humiliated himself with his inauguration speech, at which he was suspected to be drunk. He may have been ill; Castel cited typhoid fever,[95] though Gordon-Reed notes that there is no independent evidence for that diagnosis

Six weeks later, Lincoln was assassinated. Johnson was not well prepared to assume the Presidency.

Johnson implemented his own form of Presidential Reconstruction – a series of proclamations directing the seceded states to hold conventions and elections to reform their civil governments. When Southern states returned many of their old leaders, and passed Black Codes to deprive the freedmen of many civil liberties, Congressional Republicans refused to seat legislators from those states and advanced legislation to overrule the Southern actions. Johnson vetoed their bills, and Congressional Republicans overrode him, setting a pattern for the remainder of his presidency.

Much of his actions followed the plans of Lincoln as he explained them to Grant and Sherman at at City Point on March 26, 1865.

The events of the assassination resulted in speculation, then and subsequently, concerning Johnson and what the conspirators might have intended for him. In the vain hope of having his life spared after his capture, Atzerodt spoke much about the conspiracy, but did not say anything to indicate that the plotted assassination of Johnson was merely a ruse. Conspiracy theorists point to the fact that on the day of the assassination, Booth came to the Kirkwood House and left one of his cards. This object was received by Johnson’s private secretary, William A. Browning, with an inscription, “Don’t wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth.”

Johnson tried, against resistance, to follow Lincoln’s plans.

Upon taking office, Johnson faced the question of what to do with the Confederacy. President Lincoln had authorized loyalist governments in Virginia, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee as the Union came to control large parts of those states and advocated a ten percent plan that would allow elections after ten percent of the voters in any state took an oath of future loyalty to the Union. Congress considered this too lenient; its own plan, requiring a majority of voters to take the loyalty oath, passed both houses in 1864, but Lincoln pocket vetoed it.[121]

Johnson had three goals in Reconstruction. He sought a speedy restoration of the states, on the grounds that they had never truly left the Union, and thus should again be recognized once loyal citizens formed a government. To Johnson, African-American suffrage was a delay and a distraction; it had always been a state responsibility to decide who should vote. Second, political power in the Southern states should pass from the planter class to his beloved “plebeians”. This was similar to Sherman’s actions in Georgia where he would burn the homes of the rich planter class that favored secession.

The radical Republicans in Congress, led by Secretary of War Stanton, were enraged by the assassination of Lincoln and determined on revenge against the former Confederacy. Johnson opposed this and thus began his battles with the Congress.

The Republicans had formed a number of factions. The Radical Republicans sought voting and other civil rights for African Americans. They believed that the freedmen could be induced to vote Republican in gratitude fo

THis seems to have been a reasonabekl approach,r emancipation, and that black votes could keep the Republicans in power and Southern Democrats, including former rebels, out of influence. They believed that top Confederates should be punished. The Moderate Republicans sought to keep the Democrats out of power at a national level, and prevent former rebels from resuming power. They were not as enthusiastic about the idea of African-American suffrage as their Radical colleagues, either because of their own local political concerns, or because they believed that the freedman would be likely to cast his vote badly. Northern Democrats favored the unconditional restoration of the Southern states.

Johnson got into this controversy and was not adept at countering it.

Johnson was initially left to devise a Reconstruction policy without legislative intervention, as Congress was not due to meet again until December 1865.[124] Radical Republicans told the President that the Southern states were economically in a state of chaos and urged him to use his leverage to insist on rights for freedmen as a condition of restoration to the Union. But Johnson, with the support of other officials including Seward, insisted that the franchise was a state, not a federal matter.

Seward supported him and was a moderate Republican. The radicals were determined on punishment.

As Southern states began the process of forming governments, Johnson’s policies received considerable public support in the North, which he took as unconditional backing for quick reinstatement of the South. While he received such support from the white South, he underestimated the determination of Northerners to ensure that the war had not been fought for nothing. It was important, in Northern public opinion, that the South acknowledge its defeat, that slavery be ended, and that the lot of African Americans be improved. Voting rights were less important

This seems to have been a reasonable approach.

Northern public opinion tolerated Johnson’s inaction on black suffrage as an experiment, to be allowed if it quickened Southern acceptance of defeat. Instead, white Southerners felt emboldened.

I am not convinced that this is true. The South was prostrate with its economy destroyed.

At the end of the American Civil War, the devastation and disruption in the state of Georgia were dramatic. Wartime damage, the inability to maintain a labor force without slavery, and miserable weather had a disastrous effect on agricultural production. The state’s chief cash crop, cotton, fell from a high of more than 700,000 bales in 1860 to less than 50,000 in 1865, while harvests of corn and wheat were also meager.[1] The state government subsidized construction of numerous new railroad lines. White farmers turned to cotton as a cash crop, often using commercial fertilizers to make up for the poor soils they owned. The coastal rice plantations never recovered from the war.

Bartow County was representative of the postwar difficulties. Property destruction and the deaths of a third of the soldiers caused financial and social crises; recovery was delayed by repeated crop failures. The Freedmen’s Bureau agents were unable to give blacks the help they needed.

One consequence was that northern fortune seekers moved south.

During and immediately after the Civil War, many northerners headed to the southern states, driven by hopes of economic gain, a desire to work on behalf of the newly emancipated slaves or a combination of both. These “carpetbaggers”–whom many in the South viewed as opportunists looking to exploit and profit from the region’s misfortunes–supported the Republican Party, and would play a central role in shaping new southern governments during Reconstruction. In addition to carpetbaggers and freed African Americans, the majority of Republican support in the South came from white southerners who for various reasons saw more of an advantage in backing the policies of Reconstruction than in opposing them. Critics referred derisively to these southerners as “scalawags.”

The movie “Gone With the Wind” gives the southern version of this history. It was set in Georgia and other evidence suggests the conditions were much like those in the movie.

Johnson’s sympathy for the defeated South led to conflict with Congress.

According to Trefousse, “If there was a time when Johnson could have come to an agreement with the moderates of the Republican Party, it was the period following the return of Congress”. The President was unhappy about the provocative actions of the Southern states, and about the continued control by the antebellum elite there, but made no statement publicly, believing that Southerners had a right to act as they did, even if it was unwise to do so. By late January 1866, he was convinced that winning a showdown with the Radical Republicans was necessary to his political plans – both for the success of Reconstruction and for reelection in 1868. He would have preferred that the conflict arise over the legislative efforts to enfranchise African Americans in the District of Columbia, a proposal that had been defeated overwhelmingly in an all-white referendum. A bill to accomplish this passed the House of Representatives, but to Johnson’s disappointment, stalled in the Senate before he could veto it.

His struggle with Edward Stanton brought no the crisis.

Although strongly urged by Moderates to sign the Civil Rights Bill, Johnson broke decisively with them by vetoing it on March 27. In his veto message, he objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the freedmen at a time when 11 out of 36 states were unrepresented in the Congress, and that it discriminated in favor of African Americans and against whites.[138][139] Within three weeks, Congress had overridden his veto, the first time that had been done on a major bill in American history.The veto of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, often seen as a key mistake of Johnson’s presidency, convinced Moderates there was no hope of working with him.

This ended the possibility of an alliance with moderate Republicans.

In January 1867, Congressman Stevens introduced legislation to dissolve the Southern state governments and reconstitute them into five military districts, under martial law. The states would begin again by holding constitutional conventions. African Americans could vote for or become delegates; former Confederates could not. In the legislative process, Congress added to the bill that restoration to the Union would follow the state’s ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, and completion of the process of adding it to the Constitution. Johnson and the Southerners attempted a compromise, whereby the South would agree to a modified version of the amendment without the disqualification of former Confederates, and for limited black suffrage. The Republicans insisted on the full language of the amendment, and the deal fell through.

Reconstruction by the radicals was in full swing.

on March 2, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act over the President’s veto, in response to statements during the Swing Around the Circle that he planned to fire Cabinet secretaries who did not agree with him. This bill, requiring Senate approval for the firing of Cabinet members during the tenure of the president who appointed them and for one month afterwards, was immediately controversial, with some senators doubting that it was constitutional or that its terms applied to Johnson, whose key Cabinet officers were Lincoln holdovers.[149]

It was clearly unconstitutional. Just as the New York State Bill of Attainder for Trump’s taxes is another example.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was an able and hard-working man, but difficult to deal with.[150] Johnson both admired and was exasperated by his War Secretary, who, in combination with General of the Army Grant, worked to undermine the president’s Southern policy from within his own administration. Johnson considered firing Stanton, but respected him for his wartime service as secretary. Stanton, for his part, feared allowing Johnson to appoint his successor and refused to resign, despite his public disagreements with his president.

Grant favored the rights of freed slaves, but wanted no part of the position of Secretary of War. Stanton was an intemperate man. He had slandered Sherman for his efforts to assist the surrender of Joe Johnston’s army. Sherman refused to shake his hand and never spoke to him again.

Johnson and Stanton battled over the question of whether the military officers placed in command of the South could override the civil authorities. The President had Attorney General Henry Stanbery issue an opinion backing his position that they could not. Johnson sought to pin down Stanton either as for, and thus endorsing Johnson’s position, or against, showing himself to be opposed to his president and the rest of the Cabinet.

Johnson, after repeated defeats of the resolution in the House, was finally impeached in March 1868. He was acquitted by one vote. The trial lasted three months. He completed his term and later was elected to the Senate, the only ex-president to do so. He remained quite popular in the South.

What are the lessons for Trump ? Bill Clinton was impeached for lying under oath and had had his law license revoked. Additionally, he had asked/ordered cabinet members to attest to a lie. Johnson was inept in some of his advocacy for the defeated South. Trump has neither lied under oath, though accused of it by his enemies, nor shown the ineptitude of Johnson in assessing public sentiment.

This appears to be a war between the President and a Congressional House (one house) of another party. The Johnson case was somewhat similar as the opposing party did not consider him a valid President as the President had been assassinated raising him to the office. The two previous vice- presidents who had been raised to President by death also had their troubles with Congress. Tyler had his veto overridden, the first time that had happened, and Fillmore had a rough time getting the Compromise of 1850 passed.

Harrison’s death sparked a brief constitutional crisis regarding succession to the presidency, as the U.S. Constitution was unclear as to whether Vice President John Tyler should assume the office of President or merely execute the duties of the vacant office. Tyler claimed a constitutional mandate to carry out the full powers and duties of the presidency and took the presidential oath of office, setting an important precedent for an orderly transfer of presidential power when a president leaves office intra-term

Also, Tyler agreed to support an effort to craft a compromise bank bill that would meet his objections, and the cabinet developed another version of the bill.[43] Congress passed a bill based on Treasury Secretary Ewing’s proposal, but Tyler vetoed that bill as well.[44] Tyler’s second veto infuriated Whigs throughout the country, inspiring numerous anti-Tyler rallies and angry letters to the White House.[45] On September 11, members of the cabinet entered Tyler’s office one by one and resigned

After peace was restored, he (Fillmore) supported the Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson. Though he is largely obscure today, Fillmore has been praised by some, for his foreign policy, and criticized by others, for his enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act and his association with the Know Nothings.