There is a frightening symmetry going on with the Great Depression. I have previously pointed this out, for example in my review of The House of Morgan by Ron Chernow. Amity Schlaes has written about the aftermath of the crash and how the Depression developed in The Forgotten Man. Both of these books are important to understand what is happening now. Chernow’s book is a bit dated as it was written after the S&L crisis of the 80s. Another, recent book is important. That is After the Fall by Nicole Gelinas.

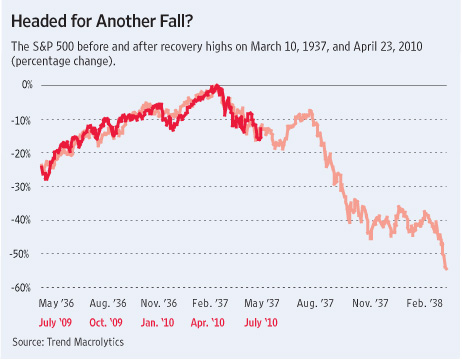

In graphic form:

Are we at 1937 ? The economy was recovering from the crash but unemployment was still high and banks had been sorted out by the FDIC.. The FDIC is one of the best measures Roosevelt devised. I am a fan of the WPA and the CCC, both of which put men to work on useful tasks. That could never happen today because of the vast web of regulations that have grown up in recent decades, most stimulated by the environmental movement. Donald Luskin, from whose blog that image comes, has some thoughts.

The stock market tells us that last year we avoided a new Great Depression—barely. It was a close call, but we’re not headed for 1932. Now, as stocks correct from their April highs and fears of a “double dip” recession mount, should we be worried about an economic relapse like 1938?

First, the good news. An important milestone was passed last week for stocks. Friday, July 2, was the 997th day since the all-time high in October 2007. That’s how many days the bear market in the Great Depression lasted, starting at the high several weeks before the Great Crash of 1929 and ending on June 1, 1932, one month before Franklin Delano Roosevelt was nominated to run for president. [Ed The bear market had ended before Roosevelt was elected.]

At the bottom in 1932, stocks (as measured by the S&P 500) had lost 86.2% from the 1929 top. Last Friday, stocks were only off 34.7% from the 2007 top. “Only”? To be sure, losing 34.7% is no buggy-ride. But to match the devastation in the Great Depression, the S&P 500 would have to fall 806 points from Friday’s level, or 78.8%.

This comparison is no idle thought experiment. In 2008 and 2009, based on what the stock market was indicating, we really were headed for a new Great Depression. At two crucial junctures in 2008 and 2009, stocks had fallen further than they did in the Great Depression the same number of days after the 1929 top.

In 1920, Harding and Coolidge faced a similar prospect to that which faced Roosevelt. There had been a bear market and a deflationary depression since the end of World War I and the cancellation of war orders. What did they do ? They cut spending and declared “a return to normalcy.” They are often mocked by the left for this but do you know what happened ? The Depression ended in 1921.

The climax came in early March 2009. Then, with the banking system still feared to be insolvent, the hasty passage of a massive deficit-busting “stimulus” bill sent the message that an all-powerful new president and Congress would just as quickly enact their strident antibusiness agenda. At the worst, stocks plunged to show a loss of 56.8% from the 2007 highs. At the comparable point in the Great Depression, stocks were off only 49%.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the new Great Depression. Chairman Ben Bernanke’s Federal Reserve announced a massive program to buy Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities to pump liquidity into the banking system. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner deftly executed “stress tests” enabling the largest banks to be recapitalized in public markets. And one agenda item at a time—socialized health-care, cap-and-trade energy tax, unionization “card check,” mortgage “cramdown”—got diluted, slowed down or stopped.

So, the failure of most of Obama’s agenda saved the economy. OK, I’ve got that.

The most worrisome analogue is the great bear market that began in March 1937. From the top stocks lost 60% of their value, making it the second worst bear market in history. Not ending until April 1942, it was the longest ever.

That’s worrisome because, as the nearby chart demonstrates, over the last year the stock market has followed a path eerily similar to 1937. First, a strong, rapid run to a recovery high—same pace, same magnitude. Then a correction—again, the same. Will we continue on the path that led the correction of 1937 into a collapse in 1938? This question would be nothing more than a technical curiosity for chartists if it weren’t for alarmingly similar economic backdrops between the two periods.

Or, maybe it was a bear market rally.

[A]fter 1937 the economy relapsed into what historians call “the recession within the Depression,” a downturn so severe that in any other context it would qualify as a depression itself.

It was triggered by a set of very specific policy mistakes. The Fed tightened by raising reserve requirements. Consumers were hit with new taxes to pay for the then-new Social Security program. Worried about excessive deficits, Roosevelt cut government spending. At the same time, his administration accelerated antibusiness rhetoric and regulation.

Sound familiar? We’re repeating some of the same mistakes right now, even as fears of a “double dip” recession mount. Antibusiness rhetoric from the Obama administration is at toxic levels, and the pending Dodd-Frank financial reform bill is the harshest regulatory initiative in a generation. Taxes are set to rise, to support new social spending such as health-care reform, and if for no other reason because no one will stop the expiration at the end of this year of the 2003 Bush tax cuts.

Amity Schlaes has some thoughts, too.

Government can spur the private sector. That’s the gist of the argument that’s in the air this summer. This week, for example, President Barack Obama said, “we’ve got much more work to do to spur stronger job growth and to keep the larger recovery moving.” Such spurring is often said to occur in a technical way, when government outlays have a so-called multiplier effect that invigorates other economic participants.

The Obama administration has a second meaning for “to spur.” It is that government entering an industry as a competitor will strengthen that industry and make it more honest. The president has said government entry into the health insurance sector will force the private companies to lower premiums.

But in reality the government isn’t a spur, either kind. It’s a competitor. And when such a big player jumps into a market, it tends to squeeze others out. Even promising industries — the Internet sector, for example — can be hurt.

This is what happened in the 1930s to the Internet equivalent of that era, the utilities industry.

Read the rest. I am still pessimistic about the economy and, as many of my friends know, am taking steps to insulate myself from the worst.