This continues the series from a lecture I have given a few times.

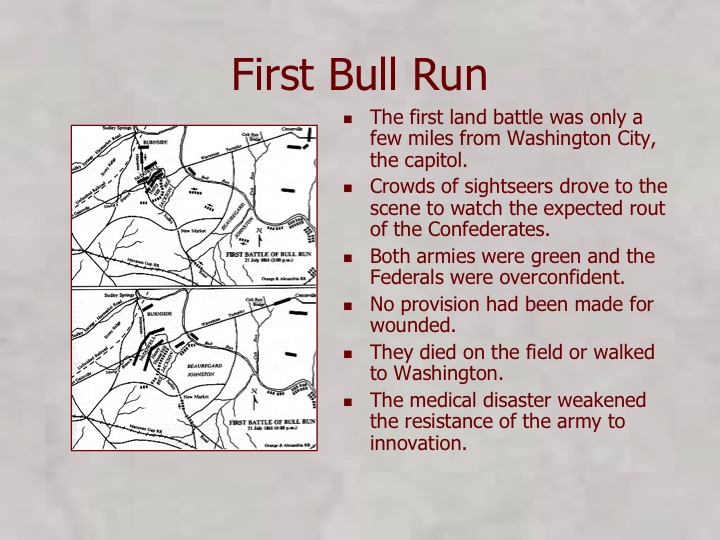

William W Keen was a student when he first served as an Army surgeon at Bull Run. That experience changed the Army medical services and gave a great deal of power to the volunteer organizations.

William Hammond quickly replaced the incompetent surgeons who had been in place when the war began. He was competent but argumentative and clashed with Stanton who became Secretary of War.

Hammond met Jonathan Letterman. Hammond worked with Letterman and Rosecrans on the design of a new ambulance wagon.

The atmosphere in the upper levels of medical services was then one of internal strife and personal conflicts. Hammond—a tall and imposing young man[12]—was no man of intrigue, nor even, according to all accounts, a very flexible person. However, the situation offered him the possibility for advancement. When Finley, the 10th Surgeon General, was fired after an argument with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Abraham Lincoln, against Stanton’s advice and the normal rules of promotion, named the 34-year-old Hammond to succeed him with the rank of brigadier general. Hammond became Surgeon General of the Army on 25 April 1862, less than a year after rejoining the army.

Lincoln liked “Men who fight” and defended his choices but Hammond was just too hard headed.

On his initiative, Letterman’s ambulance system was thoroughly tested before being extended to the whole Union. Mortality decreased significantly. Efficiency increased, as Hammond promoted people on the basis of competence, not rank or connections, and his initiatives were positive and timely.

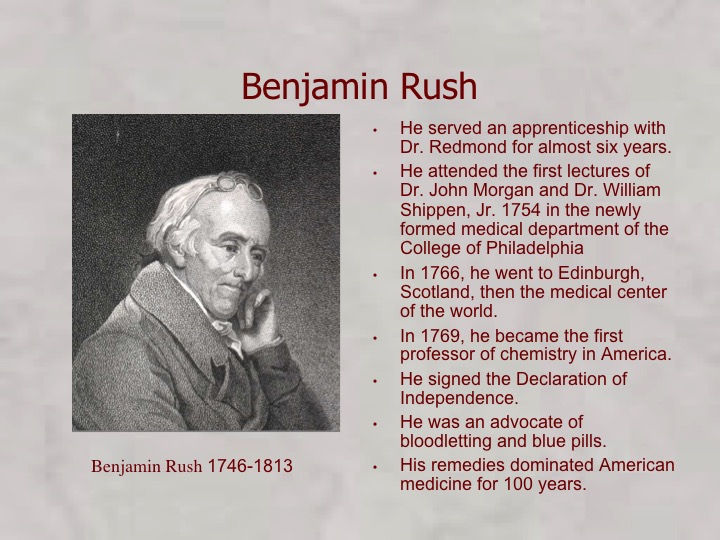

On 4 May 1863 Hammond banned the mercury compound calomel from army supplies, as he believed it to be neither safe nor effective (he was later proved correct). He thought it dangerous to make an already debilitated patient vomit. A “Calomel Rebellion” ensued, as many of his colleagues had no alternative treatments and resented the move as an infringement on their liberty of practice. Hammond’s arrogant nature did not help him solve the problem, and his relations with Secretary of War Stanton became strained. On 3 September 1863 he was sent on a protracted “inspection tour” to the South, which effectively removed him from office. Joseph Barnes, a friend of Stanton’s and his personal physician, became acting Surgeon General

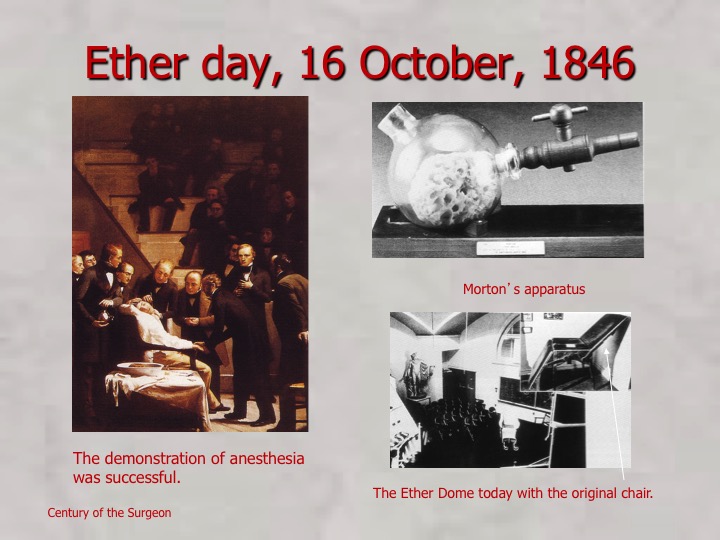

Stanton later died of an asthma attack so his “personal physician” was important to him. Calomel was “The Blue Pill” that had been advocated by Benjamin Rush. It was an ancient remedy based on the success of mercury in the treatment of syphilis dating back to Paracelsus in the 14th century. Medicine until the 20th century was quite primitive and many remedies were tried for wildly inappropriate indications.

For example, a Van Gogh painting of his doctor shows evidence of digitalis intoxication which might have caused his death. Yellow vision is one indication of overdose of digitalis (sudden death is another) and a Van Gogh painting, Portrait of Dr. Gachet shows the characteristic yellow tint plus an example of the plant held by the doctor.

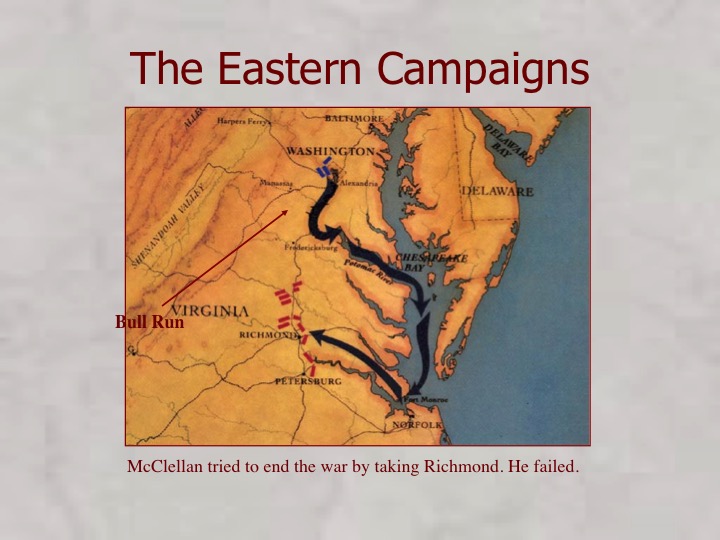

Anyway, Hammond was replaced after some of his innovations including evacuating the wounded from the Peninsula Campaign of McClellan. They were taken by ship back to large hospitals near DC.

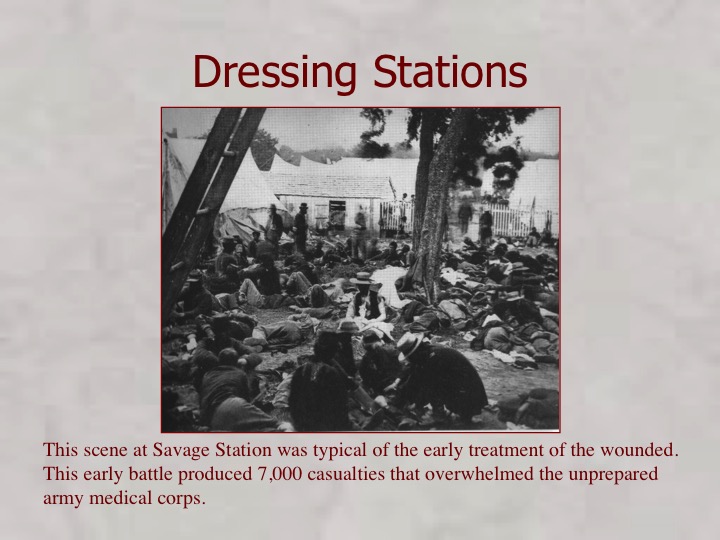

Treatment of the wounded early in the war was primitive and would soon improve under Hammond’s reforms.

The volunteer organizations began to make their influence felt and the Army was unable to resist the reforms.

Tripler, for whom the great Army hospital in Hawaii is named, was chosen by McClellan to be the chief surgeon for the Army of the Potomac. His great innovation was the “Ambulance Corps.”

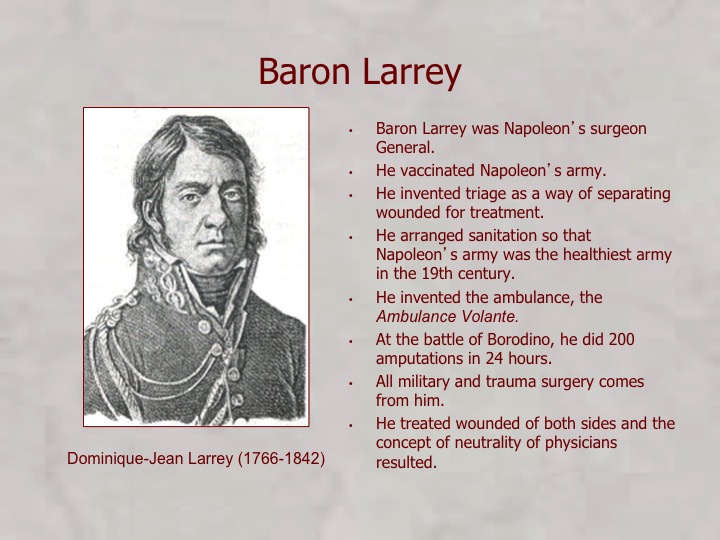

The “Ambulance Corps” restored the invention of Baron Larrey and began the reforms of the Union

To be continued