This series is a slightly annotated version of a lecture I have given in several places. One of them was at the Royal Army Medical Corps Museum in the Salisbury Plain.

Two major diseases at the time of the war were Smallpox and Malaria. Both affected large bodies of men in close quarters. Both were infectious but not water borne. Vaccination had been discovered by Edward Jenner in 1796.

In the years following 1770, at least five investigators in England and Germany (Sevel, Jensen, Jesty 1774, Rendell, Plett 1791) successfully tested a cowpox vaccine in humans against smallpox.[20] For example, Dorset farmer Benjamin Jesty[21] successfully vaccinated and presumably induced immunity with cowpox in his wife and two children during a smallpox epidemic in 1774, but it was not until Jenner’s work some 20 years later that the procedure became widely understood. Indeed, Jenner may have been aware of Jesty’s procedures and success.

By the early years of the Napoleonic Wars, Larrey had vaccinated the French Grand Army. By 1870, the French army had forgotten Larry’s work and they were decimated by smallpox while the Prussian army had been vaccinated by Billroth.

Malaria could be treated with Quinine, an extract of Cinchona bark.

Quinine occurs naturally in the bark of the cinchona tree, though it has also been synthesized in the laboratory. The medicinal properties of the cinchona tree were originally discovered by the Quechua, who are indigenous to Peru and Bolivia; later, the Jesuits were the first to bring cinchona to Europe.

The Union Army used 19 tons of cinchona bark to treat malaria in the troops. The Confederates were blockaded and had little to use. The Germans were blockaded in World War I and used their new organic chemistry industry to find alternatives, chiefly from organic dyes, like Methylene Blue.

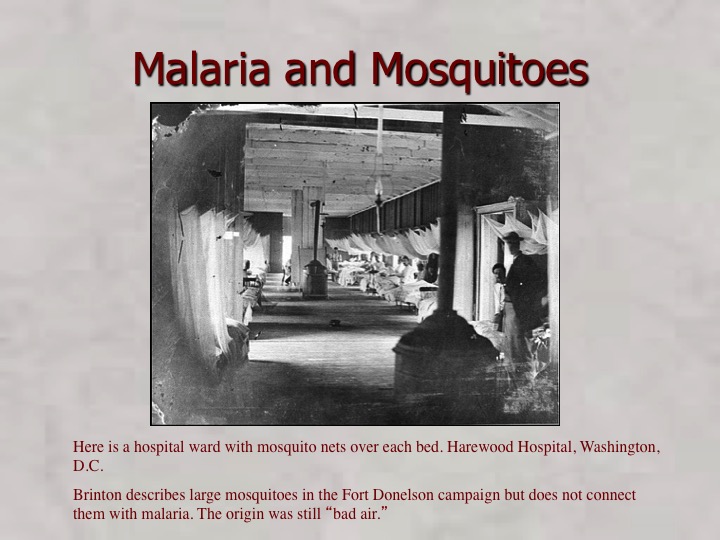

There obviously was some understanding of the role of mosquitoes in transmission of malaria as we see with the use of mosquito nets in hospitals.

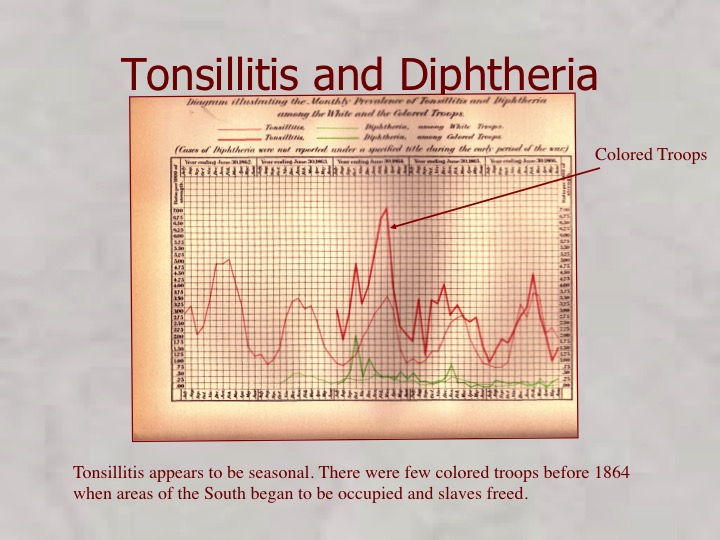

Other infectious disease were scourges although nothing was known about the cause. Tonsillitis was seasonal and diphtheria was treated with tracheostomy although I don’t know how many were done. The story of diphtheria is the story of the great triumph of bacteriology in the late 19th century. In the Civil War the only treatment was tracheostomy.

Wounds were always assumed to be infected and treated accordingly.

The treatment of extremity wounds was almost always amputation as there was no understanding of infection.

Here is an amputation tent with a pile of amputated limbs nearby. Baron Larrey, Napoleon;s surgeon personally amputated 200 limbs in 24 hours at the battle of Borodino. That was one amputation every seven minutes and was prior to the discovery of anesthesia.

There was little treatment available for wounds of the head or the body.

The wounds from a small battle are listed in The History. Head wounds were mostly fatal although a few survived.

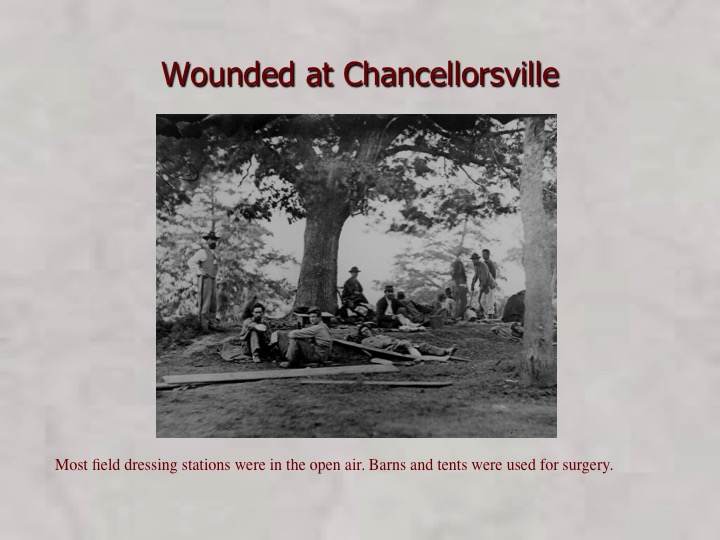

Early wound care was mostly in the open as the dressing stations were overwhelmed easily.

Saber wounds, inflicted by mounted cavalry were survivable if the skull was not penetrated and they did not become infected.

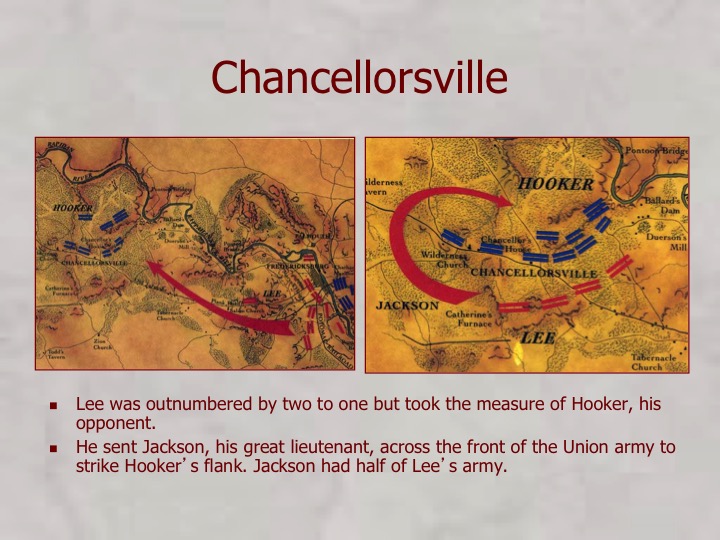

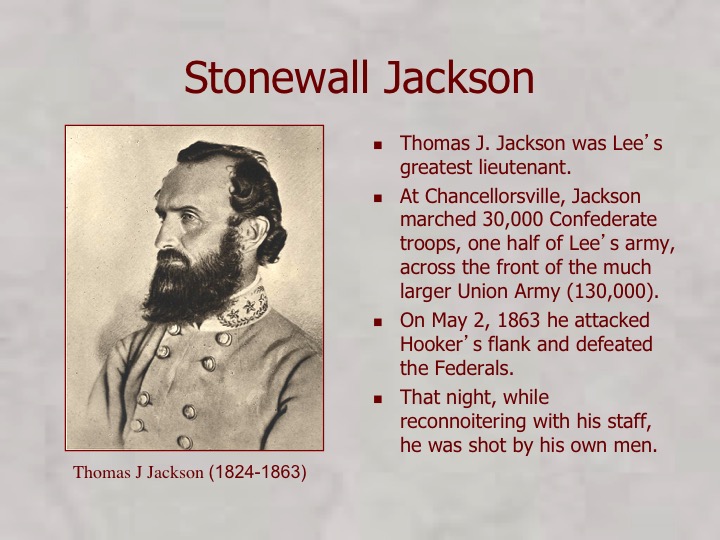

The Battle of Chancellorsville was a success for Lee but a great loss resulted as Jackson was lost.

Many believe that all chance of success in the war died with Jackson.

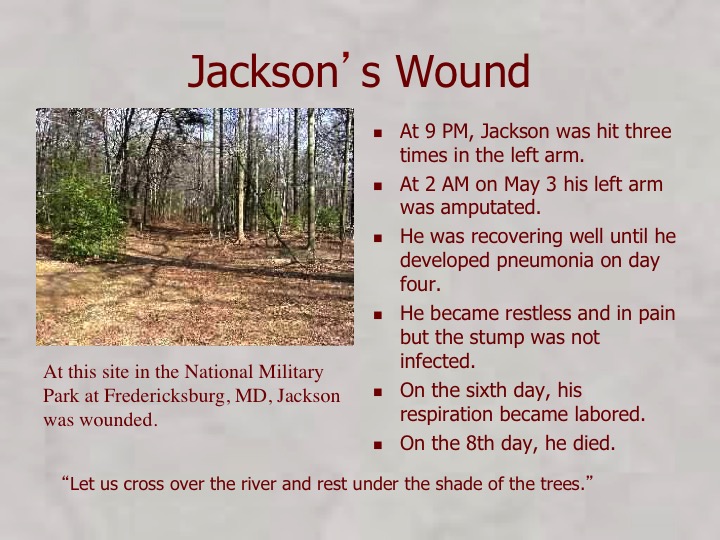

Jackson was shot by his own men as he reconnoitered the battlefield. His left arm was amputated but he did not survive. His wife was with him when he died.

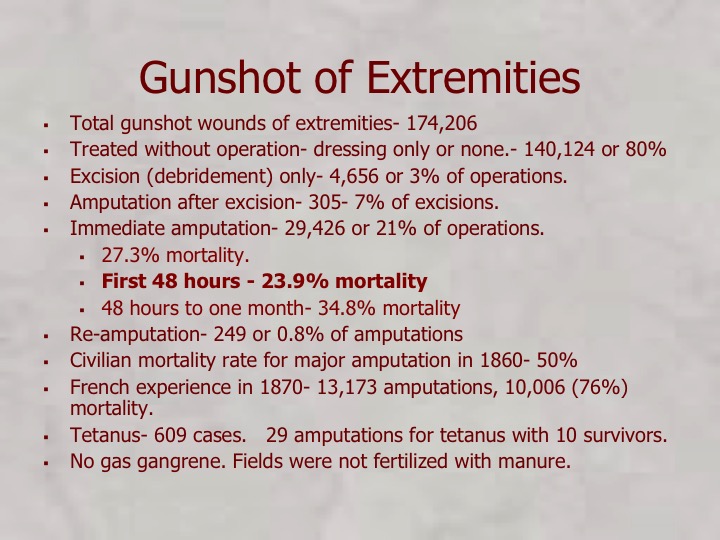

Gunshot wounds of the extremities were most of the survivors. The mortality rate of amputation was 27%. In the Franco-Prussion War, the incompetent French military surgeons had a 50% mortality rate even though antisepsis had been described three years before by Joseph Lister. Lister was treating tuberculosis of the joints, which was a common condition at the time. He found that infection was prevented by carbolic acid.

In August 1865, Lister applied a piece of lint dipped in carbolic acid solution onto the wound of a seven-year-old boy at Glasgow Infirmary, who had sustained a compound fracture after a cart wheel had passed over his leg. After four days, he renewed the pad and discovered that no infection had developed, and after a total of six weeks he was amazed to discover that the boy’s bones had fused back together, without the danger of suppuration. He subsequently published his results in The Lancet[8][9] in a series of 6 articles, running from March through July 1867.

He instructed surgeons under his responsibility to wear clean gloves and wash their hands before and after operations with 5% carbolic acid solutions. Instruments were also washed in the same solution and assistants sprayed the solution in the operating theatre. One of his additional suggestions was to stop using porous natural materials in manufacturing the handles of medical instruments.

The Germans adopted “Listerism” and the French did not. His reports were after the American Civil War although Semmelweis had tried to introduce hand washing in 1846.

Vascular injuries were untreatable and would remain so until Vietnam, when new techniques resulted in salvage of most arterial injuries.

To be continued.