There has been quite a bit of discussion on various blogs about the rising cost and declining utility of a college education, especially outside the “hard sciences.” Even the left is beginning to notice some of the problems.

And if colleges are ever going to bend the cost curve, to borrow jargon from the health care debate, it might well be time to think about vetoing Olympic-quality athletic facilities and trimming the ranks of administrators. At Williams, a small liberal arts college renowned for teaching, 70 percent of employees do something other than teach.

Complaints about athletics are old news in leftist publications but that number for non-teaching employees is an eye opener.

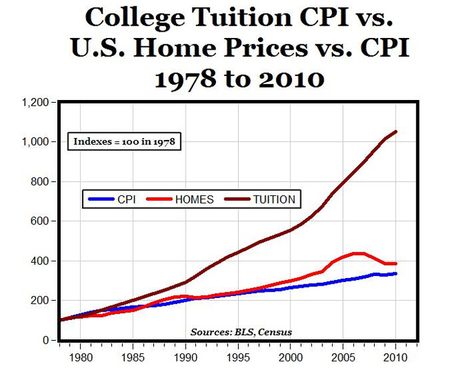

Tuition is part of the problem.

No one can look at that curve and miss the magnitude of the problem. Roger Kimball has a nice summary of the problem and the comments are almost as interesting as his post.

I went through college and medical school mostly on scholarship. I did lose my scholarship one year through the effects of too much extracurricular activity. I was taking a calculus course from this little Indian professor. He was difficult to understand but I thought we had an agreement. If I got an A on the final, I would get a B in the course. I had been delinquent in turning in homework assignments but had finally seen the light. The final exam came and, since I had finally begun to study systematically, I got the A. All my life, I had gotten by with minimal study. I was finally motivated enough to do the work necessary instead of just enough to “get by.”

Well, I went over to the Math office (In those days a small bungalow painted a dreary sunshine yellow as all the temporary university buildings were.) and the posted grades were up. I had gotten a C. I needed that B to keep a B average and my scholarship. I was doomed. I made an appointment to talk to the professor. He didn’t show up. I made another with the same result. A couple of days later, I was walking down University Avenue when I saw him across the street. I called to him and started to cross. He saw me, his eyes bulged and he started to run the other direction. I didn’t think I would improve my grade by chasing him so that was it.

In those days, there were no student loans except some private funds that I knew nothing about. My father had left high school at the age of 15 to join the Navy in World War I. I have a picture of him in his uniform. When the war ended, he wanted out of the Navy so he told them he was only 15. He never went back to school, which is a shame because he was a very bright man and could have been a very good engineer. As it was, he did pretty well in the middle years of his life and disdained education. I never saw him open a book.

My mother had graduated from high school (In 1915) and from “Business College,” which taught her to type fast enough to be a legal secretary. She could type my high school papers as I dictated them at normal speaking speed. She encouraged me to study and to think about college but nobody knew how you went about it. I knew I wanted to be an engineer and I knew I wanted to go to Cal Tech, to me the pinnacle of engineering (I still think so).

I can’t believe how naive I was about getting funding but I just didn’t know anything. My father declared himself early. He took me down to his basement bar and recreation area and had a serious talk with me. “Son, I want you to get this idea of going to college out of your head.” He wanted me to be a golf pro. One of his standard greetings to me was “Get your nose out of that book !” so this was no surprise. I had never counted on him, anyway. I didn’t know at the time that he would have one more blow to administer to my hopes.

That year, 1956, was the first year a new national scholarship program was in effect. It was called The National Merit Scholarship Program and that became my chief goal. Of course, I didn’t realize there were only 100 scholarships that year. It began with the SAT. There were no SAT prep courses then. We were lined up one day and marched into the study hall, a classroom that was unique in that it had theater style seating. We took the exam and about a month later, I was notified that I was a finalist for the National Merit Scholarship.

What I didn’t know was that a packet was sent to the parents of finalists. One item in the packet was a statement of income, although the scholarship was not based on need, apparently that was one criterion. My father refused to fill it out. It was no one’s business how much money he made, which wasn’t very much by that time. His prosperous career was pretty much behind him. A few months later, I got a letter congratulating me, and informing me that, since I did not need financial aid, I was getting a certificate of achievement. In the meantime, I had been interviewed by a Cal Tech professor who traveled to Chicago, my dorm room had been assigned and I was ready to go except for the lack of ability to pay the tuition. I look back in wonder at my own naivete in not contacting the school after my mother told me about the uncompleted financial statement. Maybe they would have helped. I just didn’t know enough.

A month or so later, I was contacted by the Chicago group of USC alumni. I was vaguely familiar with the University of Southern California and, since my prospects were otherwise dim, I accepted. I was interviewed by Robert Brooker, then a vice-president of Sears, and was awarded a full scholarship plus a $500 stipend for living expenses. My high school’s unfamiliarity with my new university was exhibited by the fact that they sent my records to UC, Berkley. I got a letter from Berkley accepting me for admission and asking me to submit an application. We finally got that straightened out and I arrived in Los Angeles about two weeks before classes began to find a place to live.

I eventually, settled in a fraternity house, Phi Gamma Delta, because, in those days at least, fraternity houses were the cheapest place to live and, of course, the fact that they asked me. I had been staying there at the request of my local sponsor, a UCLA Phi Gam alum, while I looked for an apartment. USC in those days had almost no dorms for men, unless they were football players. When I was asked to pledge, I accepted. It was a good decision in many ways (I needed socialization) but it didn’t help studying. I often wonder how I would have turned out if I had made it to Cal Tech.

Engineering at USC was a weak department but I did not take sufficient advantage of what was there. When I lost the scholarship, I was somewhat at sea. What was I to do ? The tuition was $17 a unit, about $272 a semester. I didn’t have it but, at that time, it wasn’t out of reach like it is now. I got a job. I went to work for Douglas Aircraft at what was called a Mathematician I. This was a junior engineer. I had a couple of fraternity brothers who were working there, working their way through the last year of engineering school. In those days, and the point of this stream of consciousness, is that you could work your way through school in those days, even a private university.

My job was in the wind tunnel facility. I spent most of the day with a Marchant desk calculator and the rest programming an IBM 650 computer. This was about the era when the term “bug” was first used for computer malfunctions. We were told that it derived from the fact that one of the COBOL programmers had spent weeks trying to solve a programming error only to find that a moth had gotten into the machine and was contacting random connections.

After six months at this job, I decided to go back to school at night. I was lying on the beach at Playa Del Rey (now under the take-off zone of LAX) in January talking with my roommates about my future. They were both pre-med majors. I had begun thinking about it several years before, even before dropping out of school. John Paxton, whose father was a surgeon, suggested I take a basic biology course (My high school had zero biology) and another advanced course called “Comparative Anatomy.” The latter was a junior level course and maybe too tough for me but, he said, it would be the closest thing to medical school I would find in undergraduate.

I signed up for both courses, paying the $119 tuition myself. It was a good decision. That was January 1960. A year later, I had been accepted to medical school.

Now, there is no way I could do that and the alternative would be thousands of dollars in debt.

I’m IT staff and a governor at a UK university and here of course we are going through the possibility that state funding might well more or less disappear. I happened to be looking at some US university websites to make an argument I wanted to present and was astonished also at the staff/student ratios I found.

I noticed, for example that Yale claims to have just over 11,000 students (undergrad and postgrad) and over 12,000 employees (9,000+ “staff” and 3000+ “faculty”). We have around 18,000 students and a little over 2,000 employees in total, more than half of whom I think are on academic contracts! Of course I realise Yale is in a somewhat different league to us, and is massively well endowed, but the difference was an eye opener for me!

I also noticed the other day a US headline saying that student loan debt was now, for the first time, greater than the entire country’s total credit card balances outstanbding. Clearly something needs to give in such a system.

Beyond the observations and excellent points already made, allow me to add that beyond arguably being “overcharged” in absolute terms, if one were to do a cost/benefit analysis of how much (or rather, how little) real learning takes place across the broadest part of the spectrum of American higher education (the liberal arts) the picture is even more distressing.

Read Charles Murray’s “Real Education.”

BILL

At that time, student staff ratios were low, although Cal Tech had a very high faculty student ratio. The most significant fact is that, allowing for inflation, a student could earn enough in a summer job to pay tuition and enough during the year to live. There is no longer the option to “work your way through college” except junior college. I’ve taken some computer science courses at the local junior college (Excellent, by the way) and have seen some of my classmates working as waitresses at local restaurants. In 1961, USC medical school tuition was $1200 per year. It is now over $42,000.

You’re my husband’s age, Mike, and he worked his way through a private Catholic college and those are always the most expensive. He did get a half athletic scholarship but I think he lost it. He did roofing, road building, casket making, wiring, you name it. Back then a young man with a strong back could make some serious money over summer.

I was lucky that when I went back to school in 1982, music business was still good enough that I could support myself working in house bands and took out no loans. But I knew the end of that was near and I was right.

My older son and daughter graduated from USC, which is also private, in 1988. Tuition plus room and board in a dorm was about $7500 per semester. I thought their education was pretty good. That was about the time things began to go south.